Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan

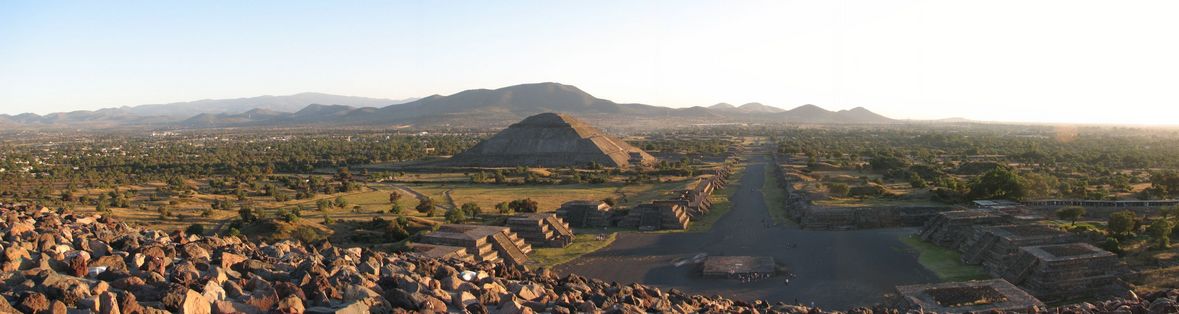

TEOTIHUACAN: Pyramids of the Moon and the Sun from the Citadel / Pirámides de la Luna y el Sol desde la Ciudadela

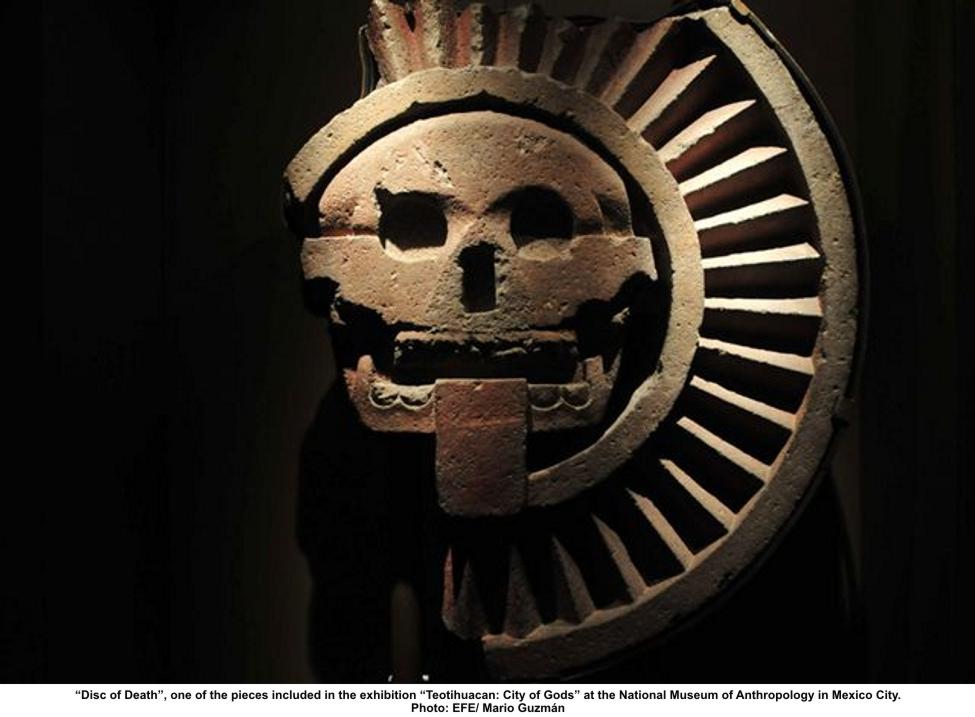

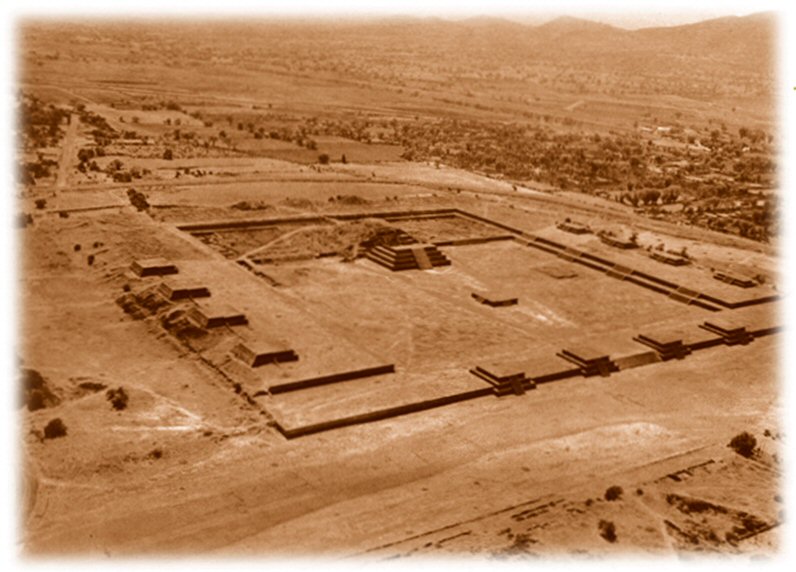

In the first century, Central Mexico saw the rise of the powerful culture of Teotihuacán. The giant city of Teotihuacán was the center of this culture, which would dominate the political history of ancient Mexico for the next 800 years. With an area of 30 square kilometers and a population of 250,000 inhabitants, Teotihuacán was the largest city of the period and one of the largest cities in the world. The people of Teotihuacán built monumental temples, streets, marketplaces and palaces and decorated them with splendid relief, murals and ground paintings.

One of the most important temples was the Temple of the Feathered Serpent. Originally painted in bright colors this temple was part of the ciudadela or citadel, a complex, which served as dwellings and administration buildings for the lords of Teotihuacán.

TEOTIHUACAN: Pyramids of the Moon and the Sun from the Citadel / Pirámides de la Luna y el Sol desde la Ciudadela

In the first century, Central Mexico saw the rise of the powerful culture of Teotihuacán. The giant city of Teotihuacán was the center of this culture, which would dominate the political history of ancient Mexico for the next 800 years. With an area of 30 square kilometers and a population of 250,000 inhabitants, Teotihuacán was the largest city of the period and one of the largest cities in the world. The people of Teotihuacán built monumental temples, streets, marketplaces and palaces and decorated them with splendid relief, murals and ground paintings.

One of the most important temples was the Temple of the Feathered Serpent. Originally painted in bright colors this temple was part of the ciudadela or citadel, a complex, which served as dwellings and administration buildings for the lords of Teotihuacán.

The Temple of the Feathered Serpent is the modern-day name for the third largest pyramid at Teotihuacan, a pre-Columbian site in central Mexico. This structure is notable partly due to the discovery in the 1980s of more than a hundred possibly-sacrificial victims found buried beneath the structure. The burials, like the structure, are dated to some time between 150 and 200 CE. The pyramid takes its name from representations of the Mesoamerican "feathered serpent" deity which covered its sides. These are some of the earliest-known representations of the feathered serpent, often identified with the much-later Aztec god Quetzalcoatl The structure is also known as the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, and the Feathered Serpent Pyramid.

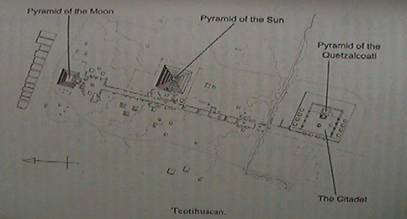

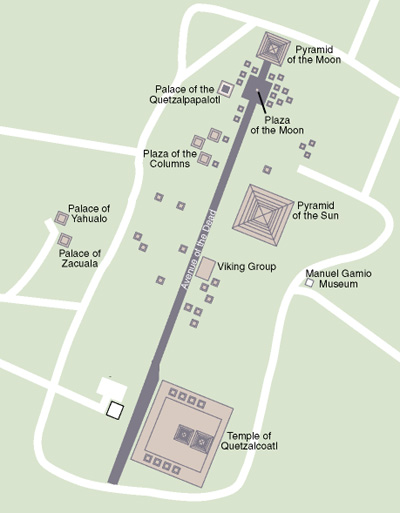

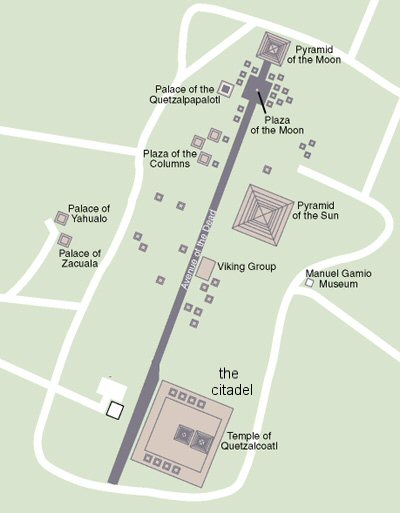

Location

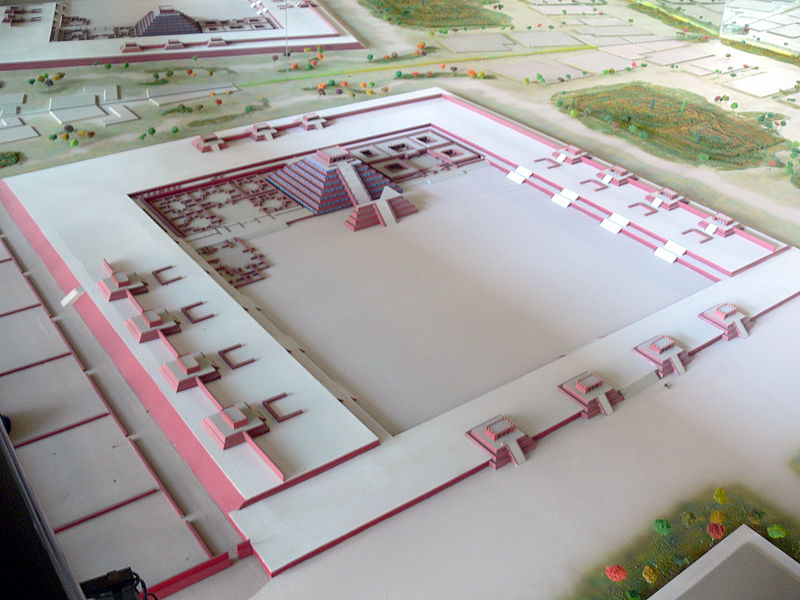

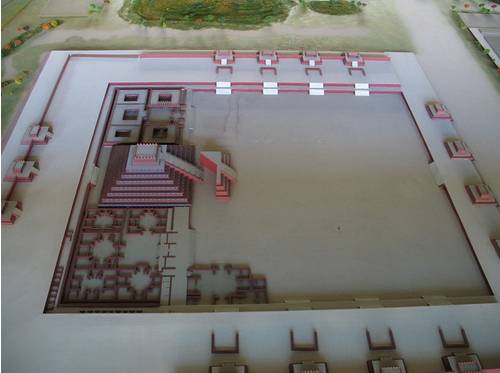

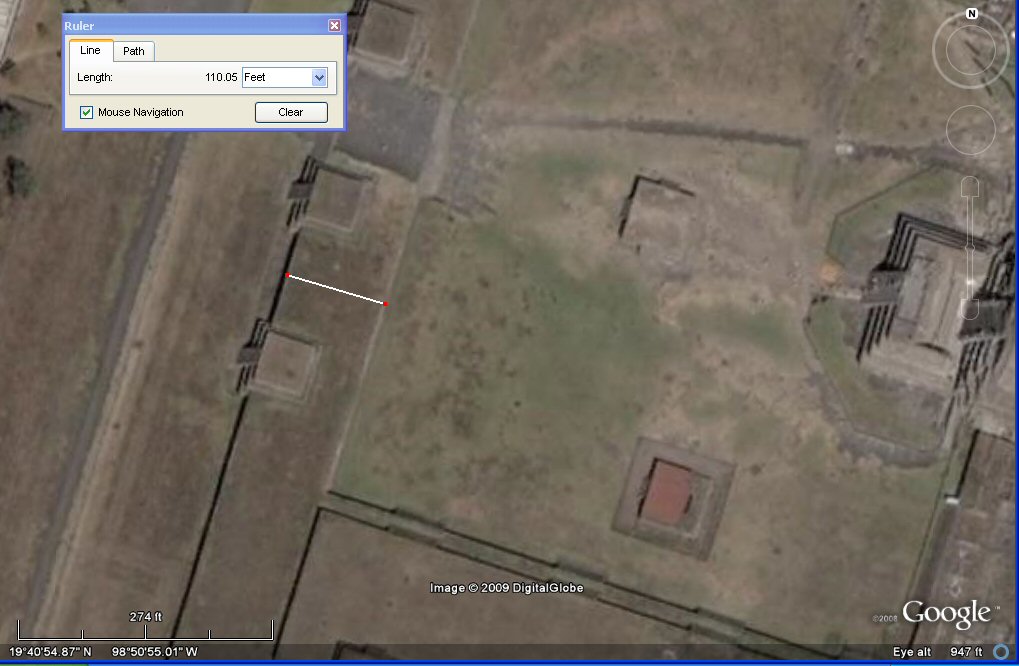

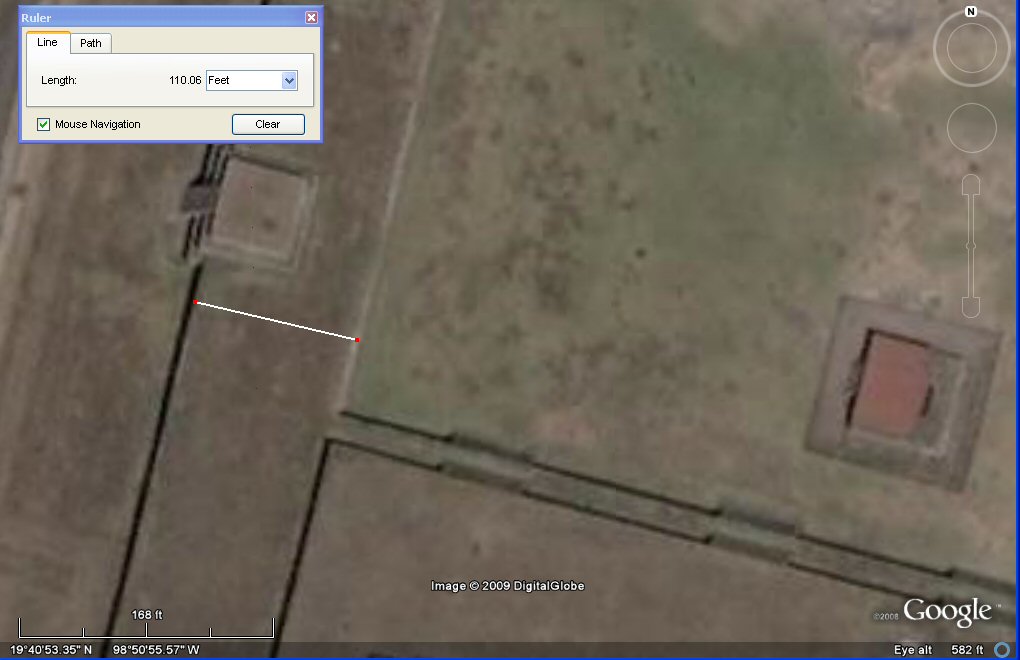

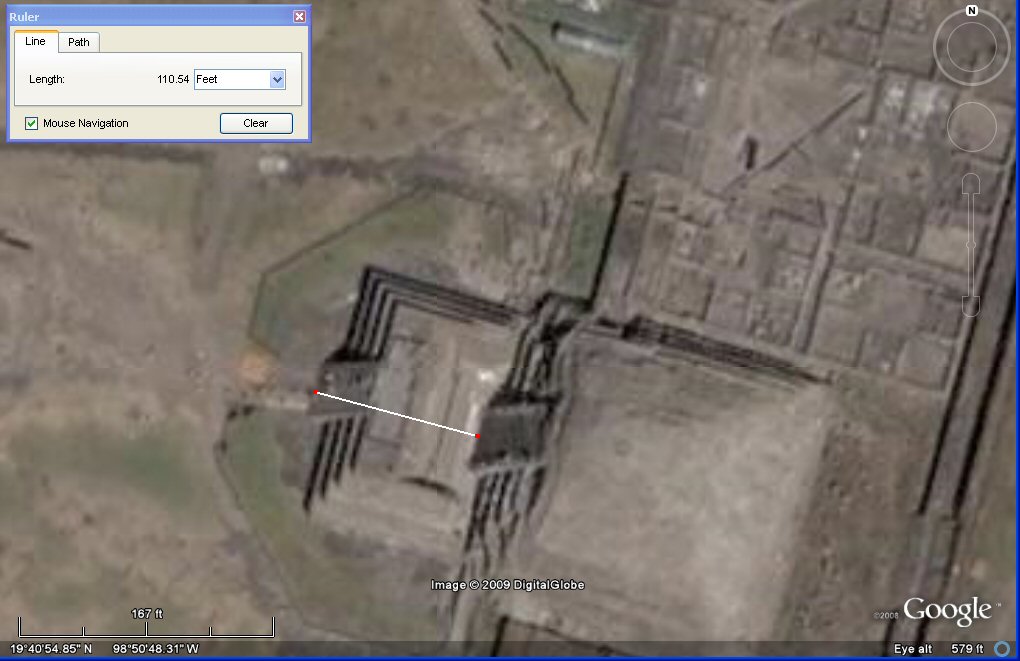

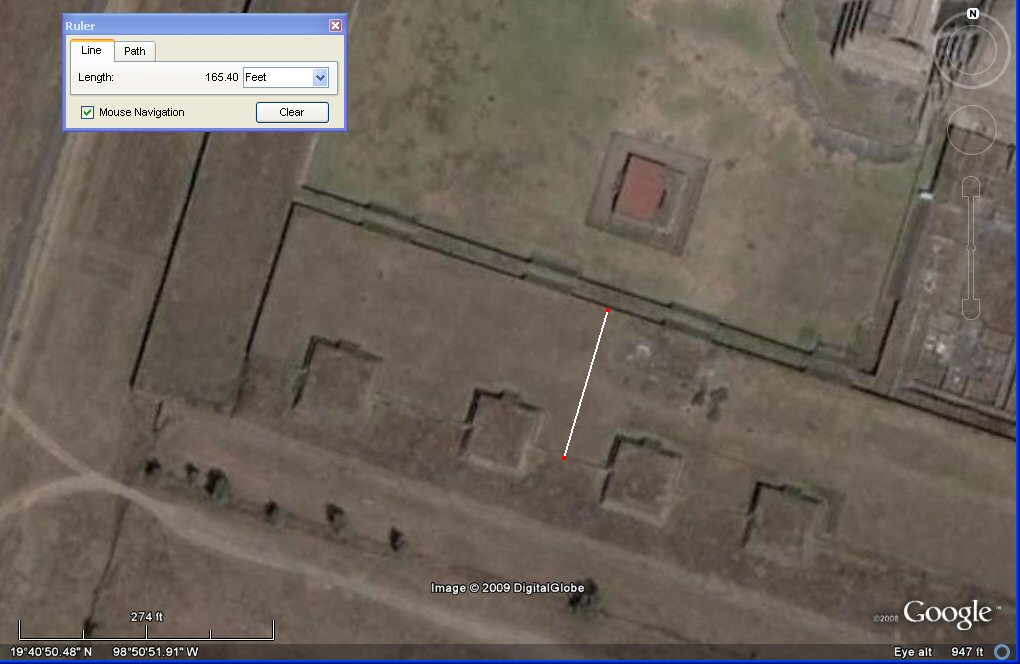

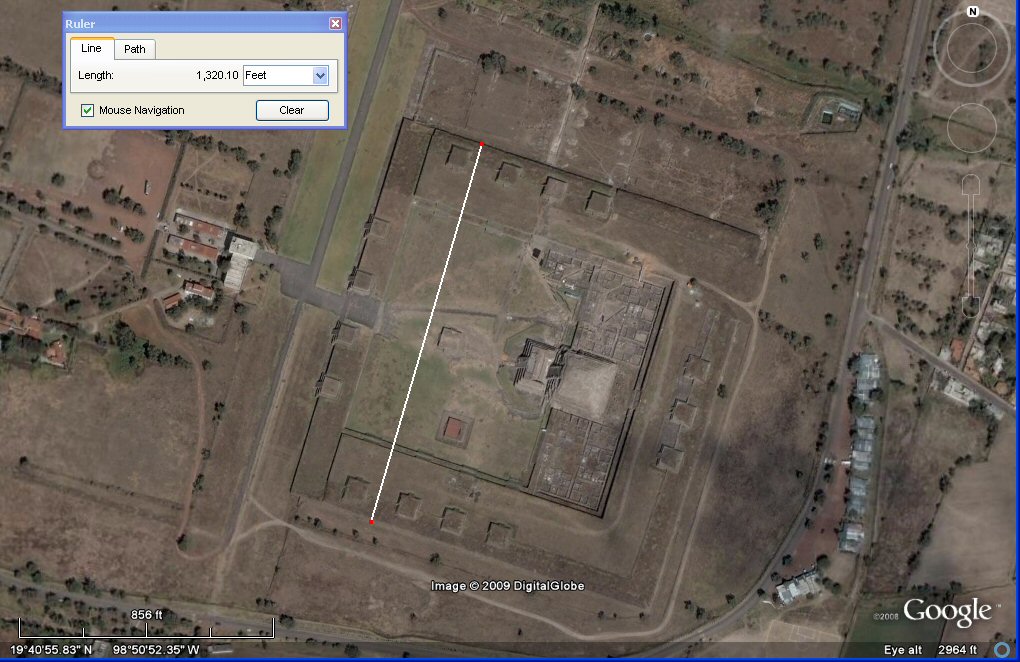

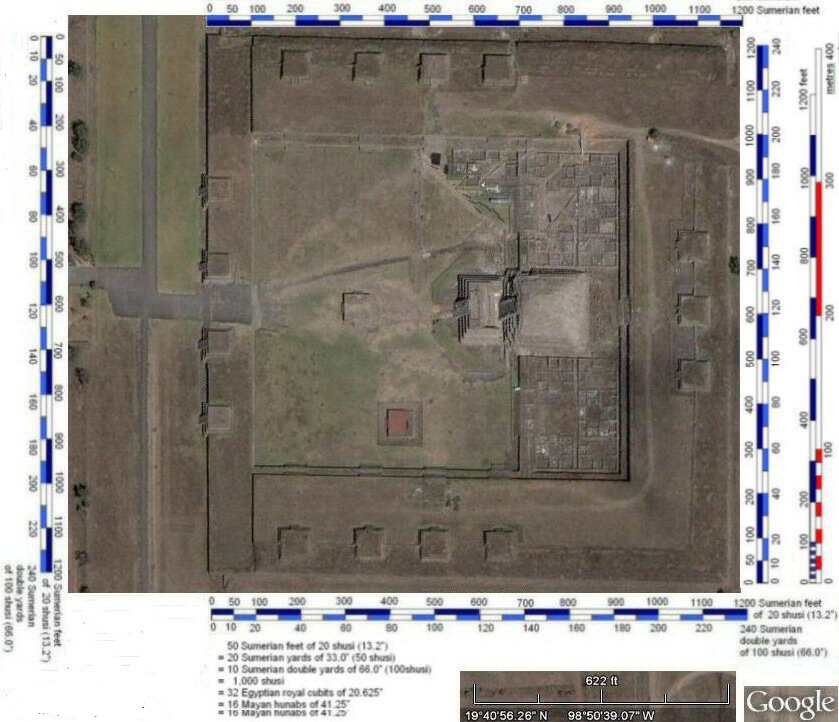

The Temple of the Feathered Serpent is located at the southern end of the Avenue of the Dead, Teotihuacan's main thoroughfare, within the Ciudadela complex. The Ciudadela (Spanish, "citadel") is a structure with high walls and a large courtyard surrounding the temple. The Ciudadela’s courtyard is massive enough that it could house the entire adult population of Teotihuacán within its walls, which was estimated to be one hundred thousand people at its peak. Within the Ciudadela there are several monumental structures, including the temple, two mansions north and south of the temple, and the Adosada platform. Built in the 4th century, the Adosada platform is located just in front (west) of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, obscuring its view.

Location

The Temple of the Feathered Serpent is located at the southern end of the Avenue of the Dead, Teotihuacan's main thoroughfare, within the Ciudadela complex. The Ciudadela (Spanish, "citadel") is a structure with high walls and a large courtyard surrounding the temple. The Ciudadela’s courtyard is massive enough that it could house the entire adult population of Teotihuacán within its walls, which was estimated to be one hundred thousand people at its peak. Within the Ciudadela there are several monumental structures, including the temple, two mansions north and south of the temple, and the Adosada platform. Built in the 4th century, the Adosada platform is located just in front (west) of the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, obscuring its view.

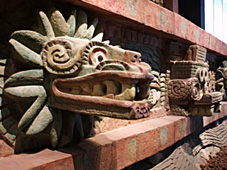

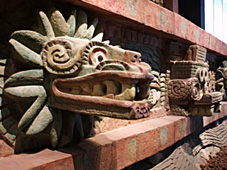

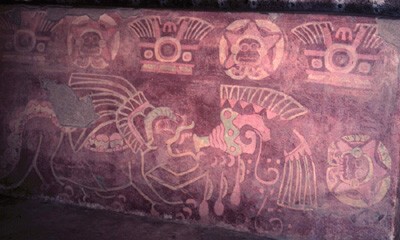

Detail of the pyramid, showing the alternating "Tlaloc" (left) and feathered serpent (right) heads. Note the long undulating feathered serpents in profile under the heads.

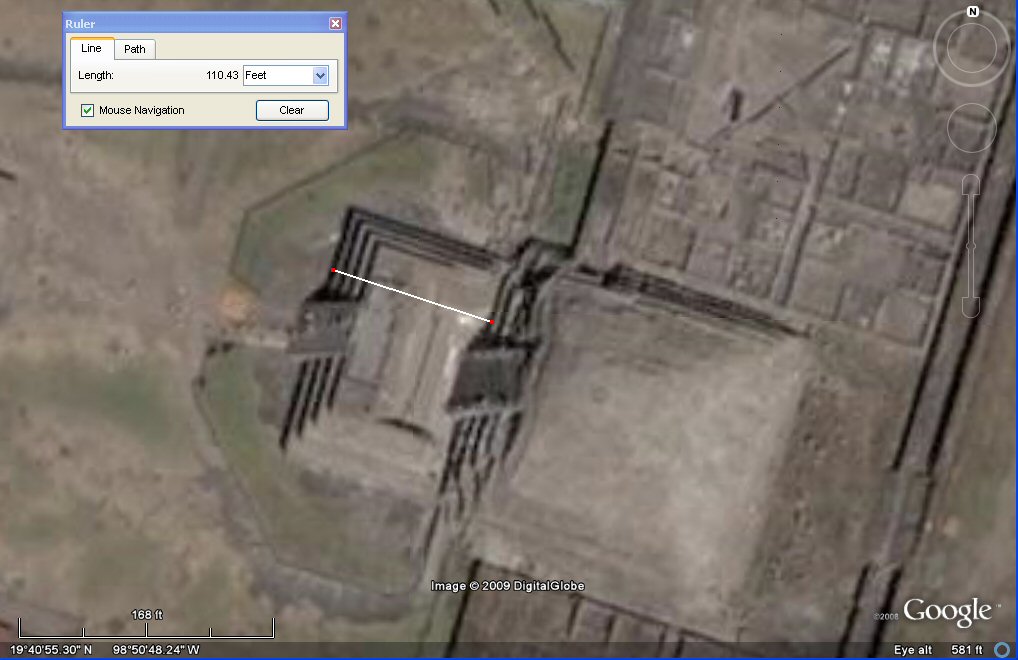

Architecture

The Feathered Serpent Pyramid is a six-level step pyramid built in the talud-tablerostyle. The outside edges of each level are decorated with feathered serpent heads alternating with those of another snake-like creature, often identified as Tlaloc. Nevertheless, Mary Ellen Miller and Karl Taube claim that these heads may represent a "war serpent",while Michael D. Coe claims, somewhat similarly, that they probably represent the "fire serpent" wearing a headdress with the Teotihuacan symbol for war. In the eyes of these figures there is a spot for obsidian glass to be put in, so when the light hits, its eyes would glimmerIn antiquity the entire pyramid was painted – the background here was blue with carved sea shells providing decoration. Under each row of heads are bas-reliefs of the full feathered serpent, in profile, also associated with water symbols. These and other designs and architectural elements are more than merely decorative, suggesting "strong ideological significance", although there is no consensus just what that significance is. Some interpret the pyramid's iconography as cosmological in scope – a myth of the origin of time or of creation – or as calendrical in nature. Others find symbols of rulership, or war and the military.

Today the pyramid is largely hidden by the Adosada platform hinting at political restructurisation of Teotihuacan during the fourth century CE, perhaps a "rejection of autocratic rule" in favour of a collective leadership. Following excavations in the early 20th century, a section of a façade on the monument's west side was discovered. This section is believed to date from the late 3rd century. Fantastic and rare carvings on the surfaces show depictions of the feathered serpent deity, other gods, and seashells on panels on either side of a staircase.

Condition and conservation

Since the structure has been been exposed to the elements for the entire duration of its history, rain and groundwater, crystallization of soluble salts on the surface, erosion, and biological growth have caused deterioration and loss of stone on the surface. Tourist visitation also accelerated the deterioration. In 2004, the Temple of Quetzalcoatl was listed in the 2004 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund. The organization provided assistance for conservation in cooperation with the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia and with help from American Express.

Architecture

The Feathered Serpent Pyramid is a six-level step pyramid built in the talud-tablerostyle. The outside edges of each level are decorated with feathered serpent heads alternating with those of another snake-like creature, often identified as Tlaloc. Nevertheless, Mary Ellen Miller and Karl Taube claim that these heads may represent a "war serpent",while Michael D. Coe claims, somewhat similarly, that they probably represent the "fire serpent" wearing a headdress with the Teotihuacan symbol for war. In the eyes of these figures there is a spot for obsidian glass to be put in, so when the light hits, its eyes would glimmerIn antiquity the entire pyramid was painted – the background here was blue with carved sea shells providing decoration. Under each row of heads are bas-reliefs of the full feathered serpent, in profile, also associated with water symbols. These and other designs and architectural elements are more than merely decorative, suggesting "strong ideological significance", although there is no consensus just what that significance is. Some interpret the pyramid's iconography as cosmological in scope – a myth of the origin of time or of creation – or as calendrical in nature. Others find symbols of rulership, or war and the military.

Today the pyramid is largely hidden by the Adosada platform hinting at political restructurisation of Teotihuacan during the fourth century CE, perhaps a "rejection of autocratic rule" in favour of a collective leadership. Following excavations in the early 20th century, a section of a façade on the monument's west side was discovered. This section is believed to date from the late 3rd century. Fantastic and rare carvings on the surfaces show depictions of the feathered serpent deity, other gods, and seashells on panels on either side of a staircase.

Condition and conservation

Since the structure has been been exposed to the elements for the entire duration of its history, rain and groundwater, crystallization of soluble salts on the surface, erosion, and biological growth have caused deterioration and loss of stone on the surface. Tourist visitation also accelerated the deterioration. In 2004, the Temple of Quetzalcoatl was listed in the 2004 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund. The organization provided assistance for conservation in cooperation with the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia and with help from American Express.

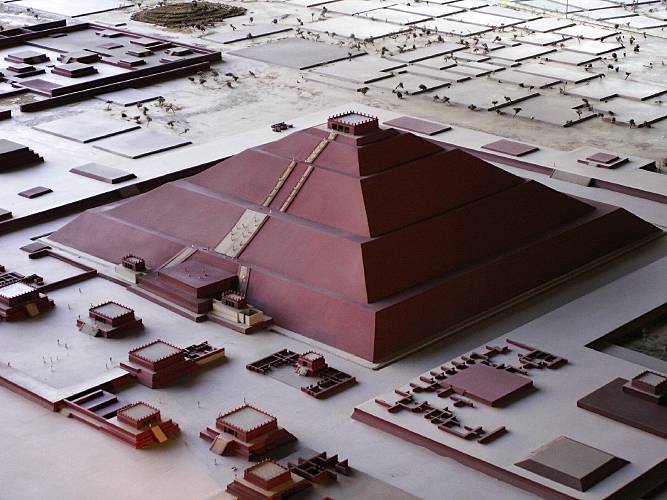

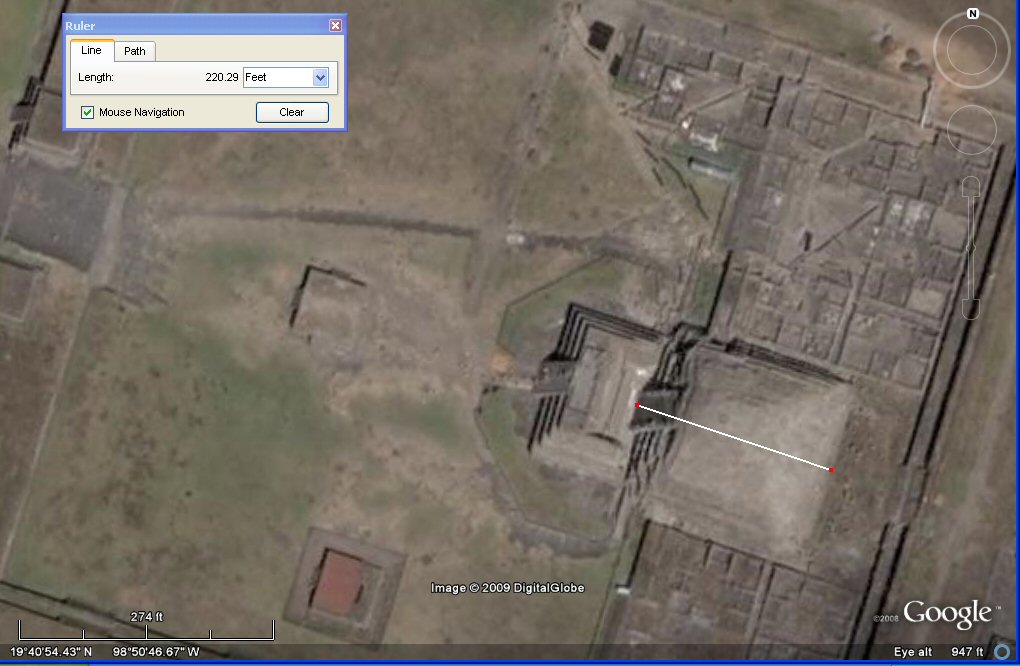

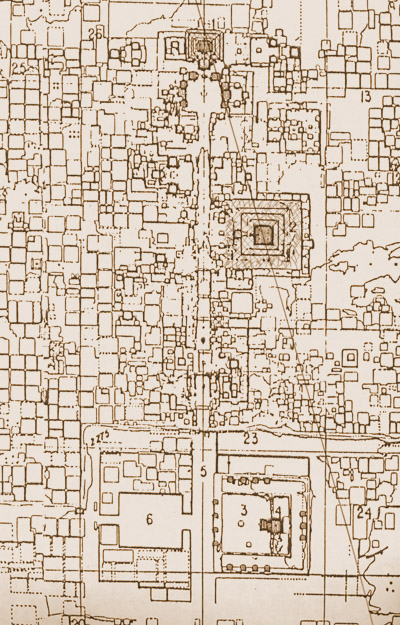

A reconstruction of the Ciudadela. The Temple of the Feathered Serpent can be seen at the upper center, with the Adosada directly in front of it.

Burials at the pyramid

Two hundred or more sacrificial burials were found at the pyramid, believed to be carried out as part of the dedication of the temple. The burials are grouped in various locations, the significance of which is not yet understood. While there are burials of both men and women, the males outnumber the females. The males were accompanied by the remains of weapons and accoutrements, such as necklaces of human teeth, that lead researchers to conclude that they were warriors, probably warriors in service to Teotihuacan rather than captives from opposing armies. The richness of the burial goods generally increases toward the center of the pyramid. At least three degrees of status have been identified, although there is no indication of a dead ruler or other obvious focal point.

Recent discoveries

On Thursday, May 26th 2011, Researchers from Mexico's National University reported that a tunnel structure had been found beneath the Temple of the Feathered Serpent using a radar device. Archaeologists there claim they have found what appears to be a series of symbols along the tunnel, 15 meters beneath the ground and 130 meters long, running eastwards and terminating in several sealed funeral chambers beneath the pyramid. The significance or orientation of the symbols is not yet understood, though it is thought they might be connected to imagery of the Mesoamerican underworld. Excavations are ongoing, and researchers are hopeful that orientation of the tunnel and position of the chambers indicate that they may contain the remains of early rulers or other high status individuals at Teotihuacan. Reseachers reported that the tunnel was believed to have been sealed in 200 CE.

Relation to the calendar

There was an apparent correlation between the Temple of the Feathered Serpent and the calendar. The pyramid also is thought to contain two hundred and sixty feathered serpent heads between the platforms. Each of these feathered serpents also contains an open area in its mouth. This open area is big enough to put a place holder in. Thus, it is believed that the people of Teotihuacán would move this place marker around the pyramid to represent the ritual calendar. When a spiritual day would arrive the people would gather within the walls of the Ciudadela and celebrate the ritual.[

Political influences

The Temple of the Feathered Serpent was not only a religious center but also a political center as well. The rulers of Teotihuacán were not only the leaders of men; they were also the spiritual leaders of the city. The two mansions near the pyramid are thought to have been occupied by powerful families. An interesting feature of the Feathered Serpent Pyramid is that there are examples of a shift in power or ideology in Teotihuacán and for the Pyramid itself. The construction of the Adosada platform came much later than the Feathered Serpent Pyramid. The Adosada platform is built directly in front of the pyramid and blocks its front view. Thus, it is thought that the political leaders lost favor or that the ideology of the Feathered Serpent Pyramid lost virtue, and so was covered up by the Adosada.

Burials at the pyramid

Two hundred or more sacrificial burials were found at the pyramid, believed to be carried out as part of the dedication of the temple. The burials are grouped in various locations, the significance of which is not yet understood. While there are burials of both men and women, the males outnumber the females. The males were accompanied by the remains of weapons and accoutrements, such as necklaces of human teeth, that lead researchers to conclude that they were warriors, probably warriors in service to Teotihuacan rather than captives from opposing armies. The richness of the burial goods generally increases toward the center of the pyramid. At least three degrees of status have been identified, although there is no indication of a dead ruler or other obvious focal point.

Recent discoveries

On Thursday, May 26th 2011, Researchers from Mexico's National University reported that a tunnel structure had been found beneath the Temple of the Feathered Serpent using a radar device. Archaeologists there claim they have found what appears to be a series of symbols along the tunnel, 15 meters beneath the ground and 130 meters long, running eastwards and terminating in several sealed funeral chambers beneath the pyramid. The significance or orientation of the symbols is not yet understood, though it is thought they might be connected to imagery of the Mesoamerican underworld. Excavations are ongoing, and researchers are hopeful that orientation of the tunnel and position of the chambers indicate that they may contain the remains of early rulers or other high status individuals at Teotihuacan. Reseachers reported that the tunnel was believed to have been sealed in 200 CE.

Relation to the calendar

There was an apparent correlation between the Temple of the Feathered Serpent and the calendar. The pyramid also is thought to contain two hundred and sixty feathered serpent heads between the platforms. Each of these feathered serpents also contains an open area in its mouth. This open area is big enough to put a place holder in. Thus, it is believed that the people of Teotihuacán would move this place marker around the pyramid to represent the ritual calendar. When a spiritual day would arrive the people would gather within the walls of the Ciudadela and celebrate the ritual.[

Political influences

The Temple of the Feathered Serpent was not only a religious center but also a political center as well. The rulers of Teotihuacán were not only the leaders of men; they were also the spiritual leaders of the city. The two mansions near the pyramid are thought to have been occupied by powerful families. An interesting feature of the Feathered Serpent Pyramid is that there are examples of a shift in power or ideology in Teotihuacán and for the Pyramid itself. The construction of the Adosada platform came much later than the Feathered Serpent Pyramid. The Adosada platform is built directly in front of the pyramid and blocks its front view. Thus, it is thought that the political leaders lost favor or that the ideology of the Feathered Serpent Pyramid lost virtue, and so was covered up by the Adosada.

Temple of the Feathered Serpent (TeotihuacanThe Temple of the Feathered Serpent is the modern-day name for the third largest pyramid at Teotihuacan. The structure is particularly notable due to the 200 or more sacrificial victims found buried beneath the structure. Scientists date the burials to some time between 150 and 200 CE. The pyramid’s name comes from representations of the Mesoamerican “feathered serpent” deity covering the sides of the building. These are thought to be some of the earliest-known representations of the feathered serpent, often identified with the much-later Aztec god Quetzalcoatl. The structure is also known as the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, and the Feathered Serpent Pyramid.

The Feathered Serpent Pyramid is a six-level step pyramid built in the talud-tablero style. Feathered serpent heads alternating with those of another snake-like creature, often identified with Tlaloc, the lightning/rain deity, adorn the outer edges of each level of the structure. Mary Ellen Miller and Karl Taube claim the heads represent a "war serpent", while Michael D. Coe claims, that the heads probably represent the "fire serpent" wearing a headdress with the Teotihuacan symbol for war. In the eyes of these figures there is a spot for obsidian glass, causing the eyes to glimmer with light. In antiquity, the builders probably painted entire pyramid – the background most likely blue decorated with carved sea shells.

Under each row of heads bas-reliefs of the full feathered serpent, in profile, also exist. These and other designs and architectural elements suggest a "strong ideological significance" for the building overall; there is no consensus just what that significance is. Some interpret the pyramid's iconography as cosmological – a myth of the origin of time or of creation represented in stone – or a calendrical timekeeper. Others find symbols of rulership, war and the military.

On Thursday, May 26th 2011, researchers from Mexico's National University reported the discovery of a tunnel structure beneath the Temple of the Feathered Serpent using a radar device. Archaeologists claimed also the discovery of what appears to be a series of symbols along the tunnel, 15 meters beneath the ground and 130 meters long, running eastwards and terminating in several sealed potential “funeral”chambers beneath the pyramid. The significance or orientation of the symbols is not yet understood.

Excavations remain ongoing, and researchers hope that the orientation of the tunnel and position of the chambers indicate potential remains of early rulers or other high status individuals at Teotihuacan

The Feathered Serpent Pyramid is a six-level step pyramid built in the talud-tablero style. Feathered serpent heads alternating with those of another snake-like creature, often identified with Tlaloc, the lightning/rain deity, adorn the outer edges of each level of the structure. Mary Ellen Miller and Karl Taube claim the heads represent a "war serpent", while Michael D. Coe claims, that the heads probably represent the "fire serpent" wearing a headdress with the Teotihuacan symbol for war. In the eyes of these figures there is a spot for obsidian glass, causing the eyes to glimmer with light. In antiquity, the builders probably painted entire pyramid – the background most likely blue decorated with carved sea shells.

Under each row of heads bas-reliefs of the full feathered serpent, in profile, also exist. These and other designs and architectural elements suggest a "strong ideological significance" for the building overall; there is no consensus just what that significance is. Some interpret the pyramid's iconography as cosmological – a myth of the origin of time or of creation represented in stone – or a calendrical timekeeper. Others find symbols of rulership, war and the military.

On Thursday, May 26th 2011, researchers from Mexico's National University reported the discovery of a tunnel structure beneath the Temple of the Feathered Serpent using a radar device. Archaeologists claimed also the discovery of what appears to be a series of symbols along the tunnel, 15 meters beneath the ground and 130 meters long, running eastwards and terminating in several sealed potential “funeral”chambers beneath the pyramid. The significance or orientation of the symbols is not yet understood.

Excavations remain ongoing, and researchers hope that the orientation of the tunnel and position of the chambers indicate potential remains of early rulers or other high status individuals at Teotihuacan

Pyramid of the Moon

The Pyramid of the Moon is the second largest pyramid in Teotihuacan after the Pyramid of the Sun. The structure is located in the northern part of Teotihuacan and mimics the contours of the mountain Cerro Gordo, just north of the site. Some call the pyramid Tenan, in Nahuatl, meaning "mother or protective stone." The Pyramid of the Moon covers a structure older than the Pyramid of the Sun, existing prior to 200 AD.

Scientists think the Pyramid's construction fell between 200 and 450 AD, which completed the bilateral symmetry of the complex. A slope in front of the staircase gives access to the Avenue of the Dead. Archaeologists believe that a platform atop the pyramid saw use as a ceremonial place in honor of the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan, the goddess of water, fertility, the earth, and creation. The platform and the sculpture found at the pyramid's bottom are thus dedicated to The Great Goddess.

Opposite the Great Goddess's altar is the Plaza of the Moon. The Plaza contains a central altar and an original construction with internal divisions, consisting of four rectangular and diagonal bodies that formed what is known as the "Teotihuacan Cross."

Recently, archaeologists excavated beneath the Pyramid of the Moon. Tunnels dug into the structure revealed that the pyramid underwent at least six renovations and each new addition was larger and covered the previous structure.

Piramide de la Luna - Pyramid of the Moon:

Scientists think the Pyramid's construction fell between 200 and 450 AD, which completed the bilateral symmetry of the complex. A slope in front of the staircase gives access to the Avenue of the Dead. Archaeologists believe that a platform atop the pyramid saw use as a ceremonial place in honor of the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan, the goddess of water, fertility, the earth, and creation. The platform and the sculpture found at the pyramid's bottom are thus dedicated to The Great Goddess.

Opposite the Great Goddess's altar is the Plaza of the Moon. The Plaza contains a central altar and an original construction with internal divisions, consisting of four rectangular and diagonal bodies that formed what is known as the "Teotihuacan Cross."

Recently, archaeologists excavated beneath the Pyramid of the Moon. Tunnels dug into the structure revealed that the pyramid underwent at least six renovations and each new addition was larger and covered the previous structure.

Piramide de la Luna - Pyramid of the Moon:

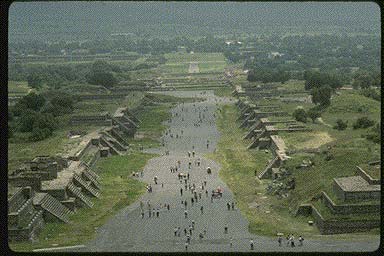

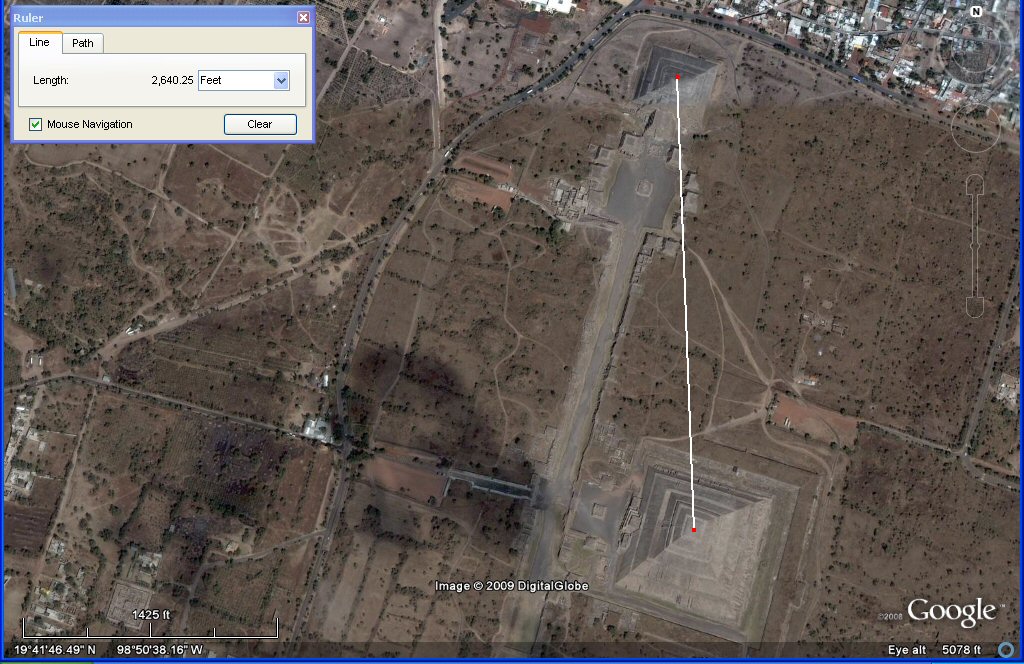

The Pyramid of the moon at Teotihuacan appears to be as tall as the Pyramid of the Sun due to the fact that it is built on higher ground. This pyramid was built slightly later than the Pyramid of the Sun, perhaps around the time the first was finished. The top of the Pyramid of the Moon provides the best overall view of Teotihuacan. The sight of the ruins stretching both sides of the mile long Avenue of the Dead opens ones eyes to how truly great this city once was.

Pyramid of the Moon

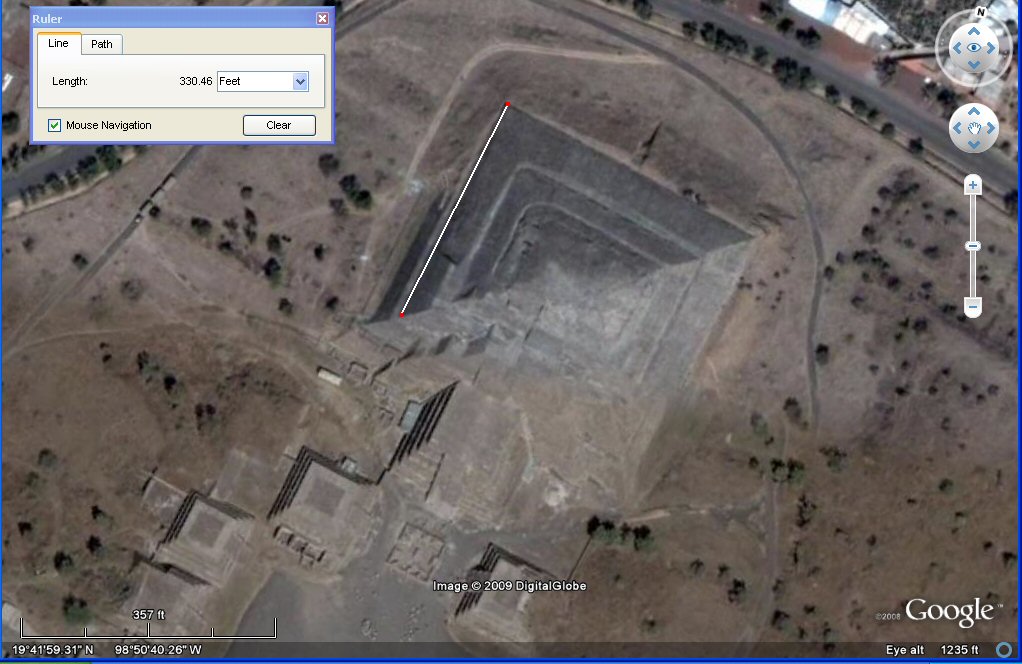

Although this pyramid is smaller than that of the Sun, it was constructed on higher ground and its peak is roughly at the same height. Here there are four tiers, and some of the steps are so large that climbing the pyramid requires much effort. It is worth at least climbing to the first platform though, for the view directly down the Calle de los Muertos is highly memorable.

Although this pyramid is smaller than that of the Sun, it was constructed on higher ground and its peak is roughly at the same height. Here there are four tiers, and some of the steps are so large that climbing the pyramid requires much effort. It is worth at least climbing to the first platform though, for the view directly down the Calle de los Muertos is highly memorable.

The Moon Pyramid is located at the northern end of the Avenue of the Dead, which was the main axis of the city. The pyramid, facing south, was built as the principal monument of the Moon Pyramid complex. The five-tiered platform was attached to the front of the Moon Pyramid.

The Pyramid of the Moon is smaller and faces a plaza at the northern end of the avenue. No cave or other feature has been discovered in its interior. Its form may be patterned on that of the sacred mountain to the north, the Cerro Gordo. The summit provides about the same range of view as you from its larger neighbor because the moon pyramid is built on higher ground. The perspective straight down the Avenue of the Dead is magnificent (and featured in the photo at the top of this article).

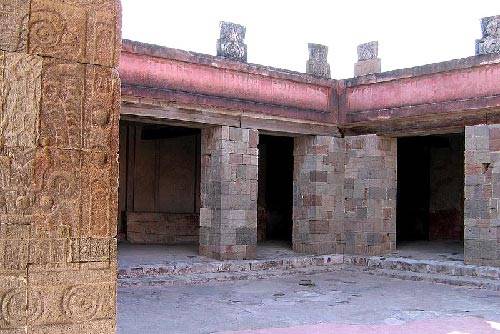

The plaza fronted by the Pyramid of the Moon is surrounded by little temples and by the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl or Quetzal-Mariposa (Quetzal-Butterfly) on the left (west) side. The Palace of Quetzalpapalotl lay in ruins until the 1960s, when restoration work began. Today, it reverberates with its former glory, as figures of Quetzal-Mariposa (a mythical, exotic bird-butterfly) appear painted on walls or carved in the pillars of the inner court. Behind the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl is the Palace of the Jaguars, complete with murals showing jaguars and some frescoes

The plaza fronted by the Pyramid of the Moon is surrounded by little temples and by the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl or Quetzal-Mariposa (Quetzal-Butterfly) on the left (west) side. The Palace of Quetzalpapalotl lay in ruins until the 1960s, when restoration work began. Today, it reverberates with its former glory, as figures of Quetzal-Mariposa (a mythical, exotic bird-butterfly) appear painted on walls or carved in the pillars of the inner court. Behind the Palace of Quetzalpapalotl is the Palace of the Jaguars, complete with murals showing jaguars and some frescoes

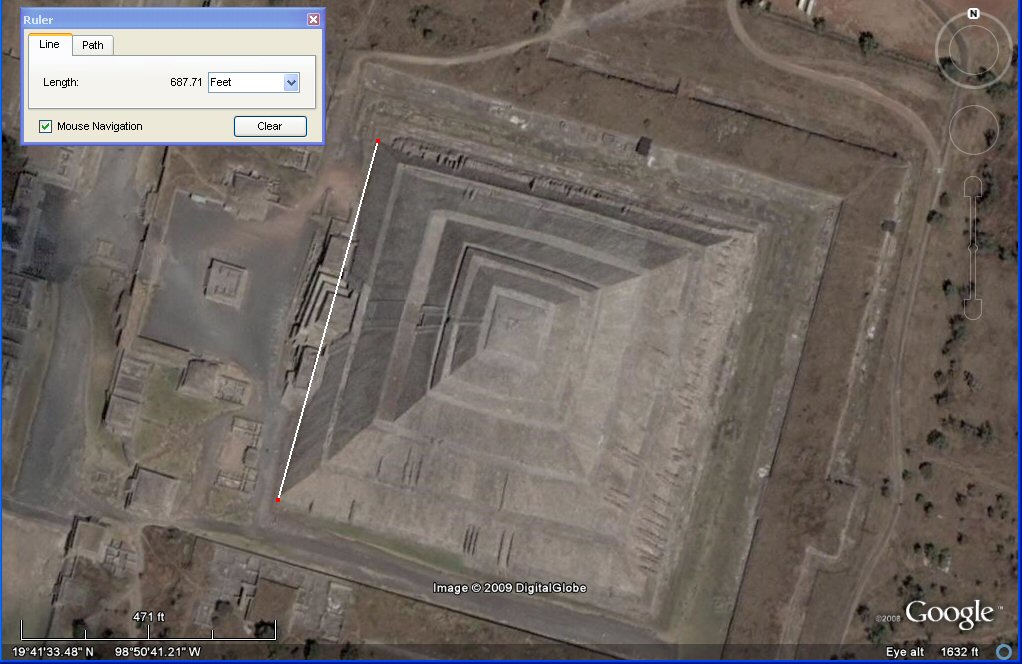

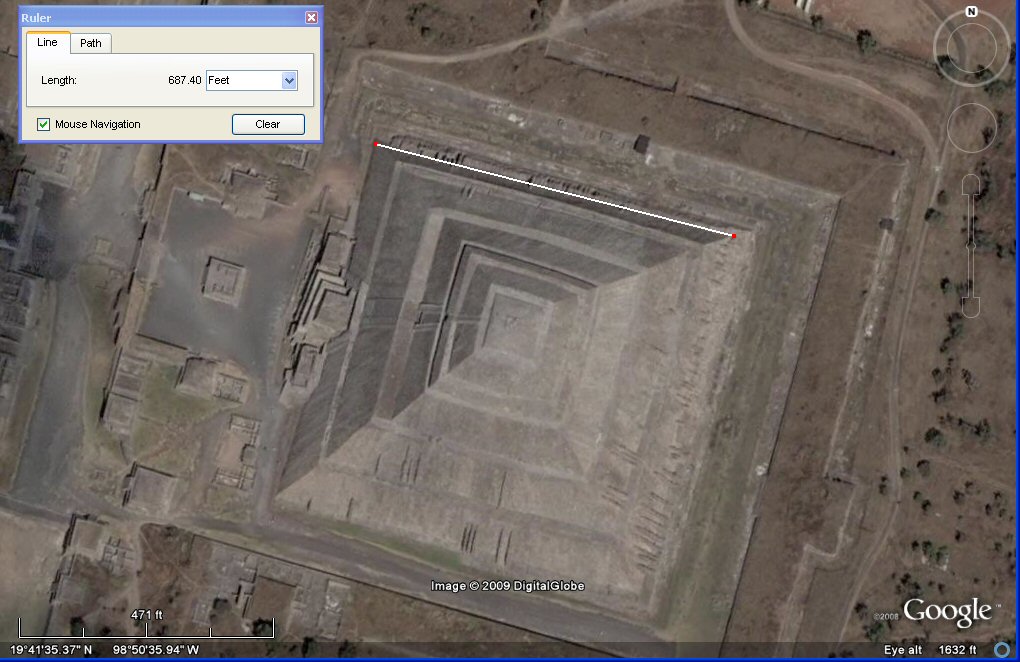

Pyramid of the Sun

The Pyramid of the Sun is the largest building in Teotihuacan and one of the largest in greater Mesoamerica. Found along the Avenue of the Dead, in between the Pyramid of the Moon and the Ciudadela, and in the shadow of the massive mountain Cerro Gordo, the pyramid is part of a large complex in the heart of the city. The name Pyramid of the Sun comes from the Aztecs, a people that visited the city of Teotihuacán centuries after the original inhabitants abandoned the site; the name given to the pyramid by the Teotihuacanos is unknown. Teotihuacan literally means, in the Nahua native languages, “The Place where Men became gods.” Little is actually known about the site due to limited organic finds and artifacts.

The orientation of the structure may hold anthropological clues to the function of the pyramid. The Pyramid of the Sun is oriented slightly northwest of the horizon point of the setting sun on two days a year, August 12 and April 29. The day of August 12 is significant because the day also marks the date of the beginning of the present era and the initial day of the Maya long count calendar, 4 Ahau, 8 Cumku, or 3314 BC. Archaeologists state that the site thrived around 100 AD or so, but no clear evidence exists to suggest that the buildings at the site rose up around that time. In addition, many important astrological events linked with agriculture can be viewed from atop the pyramid, probably lending the structure its name, as the sun represented a vital symbol to agriculturally driven societies (light provided food for plants (photosynthesis), but too much sun with no rain caused drought).

Scientists discovered that the pyramid actually lay atop a man-made tunnel leading to a "cave" located six meters down beneath the center of the structure. Originally, archaeologists speculated the cave comprised a naturally formed lava tube and interpreted the site as the place of Chicomoztoc, the place of human origin according to long standing Nahua legends. Recent excavations suggest that the space is man-made, possibly serving as a royal tomb, although no proof exists to indicate that idea. Recently scientists used muon detectors to try to find other chambers within the interior of the pyramid.

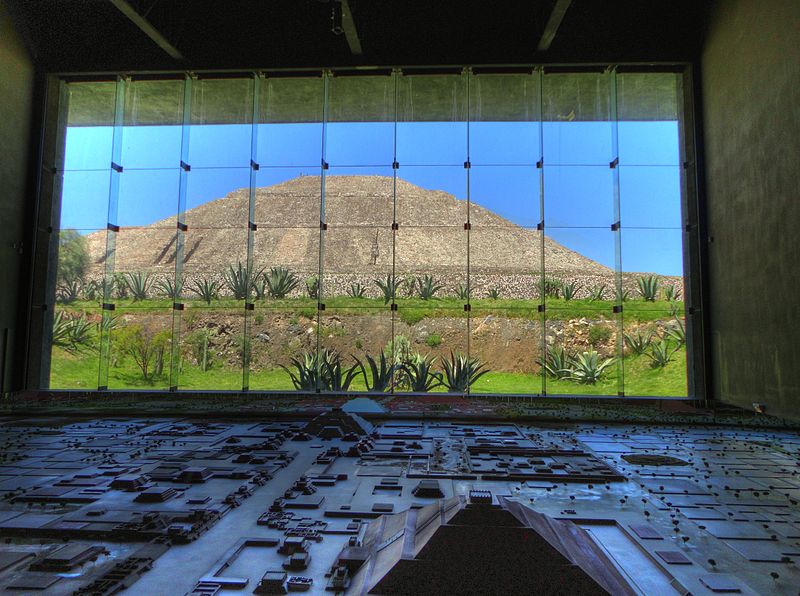

The Teotihuacan site is one of the most visited archaeological sites in Mexico. An entire diorama layout of the city lies open to the public at the site museum

The orientation of the structure may hold anthropological clues to the function of the pyramid. The Pyramid of the Sun is oriented slightly northwest of the horizon point of the setting sun on two days a year, August 12 and April 29. The day of August 12 is significant because the day also marks the date of the beginning of the present era and the initial day of the Maya long count calendar, 4 Ahau, 8 Cumku, or 3314 BC. Archaeologists state that the site thrived around 100 AD or so, but no clear evidence exists to suggest that the buildings at the site rose up around that time. In addition, many important astrological events linked with agriculture can be viewed from atop the pyramid, probably lending the structure its name, as the sun represented a vital symbol to agriculturally driven societies (light provided food for plants (photosynthesis), but too much sun with no rain caused drought).

Scientists discovered that the pyramid actually lay atop a man-made tunnel leading to a "cave" located six meters down beneath the center of the structure. Originally, archaeologists speculated the cave comprised a naturally formed lava tube and interpreted the site as the place of Chicomoztoc, the place of human origin according to long standing Nahua legends. Recent excavations suggest that the space is man-made, possibly serving as a royal tomb, although no proof exists to indicate that idea. Recently scientists used muon detectors to try to find other chambers within the interior of the pyramid.

The Teotihuacan site is one of the most visited archaeological sites in Mexico. An entire diorama layout of the city lies open to the public at the site museum

Piramide del Sol - Pyramid of the Sun:

The Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan was built in the first century AD. It has a base ten feet shorter (on each side) than the Great Pyramid of Cheops, and a volume of 2.5 million tones of stone and earth used in its construction. The alignment of this pyramid was designed to coincide with the two days a year (May 19th and July 25th) when the Sun would be directly over the top of the pyramid at noon. The East facade directly faces the rising Sun, and the West facade directly faces the Sun as it sets. In 1971 archeologists stumbled across a clover leaf shaped cave (closed to the public) believed to have been formed by a subterranean spring. Speculation abounds about this area being used as some kind of inner sanctuary or sacred place.

The Pyramid of the Sun at Teotihuacan was built in the first century AD. It has a base ten feet shorter (on each side) than the Great Pyramid of Cheops, and a volume of 2.5 million tones of stone and earth used in its construction. The alignment of this pyramid was designed to coincide with the two days a year (May 19th and July 25th) when the Sun would be directly over the top of the pyramid at noon. The East facade directly faces the rising Sun, and the West facade directly faces the Sun as it sets. In 1971 archeologists stumbled across a clover leaf shaped cave (closed to the public) believed to have been formed by a subterranean spring. Speculation abounds about this area being used as some kind of inner sanctuary or sacred place.

Temple of Quetzalcoatl / Piramide de Quetzalcoatl

Temple of Quetzalcoatl, view of inner and outer pyramid (it was rebuilt 7 times)

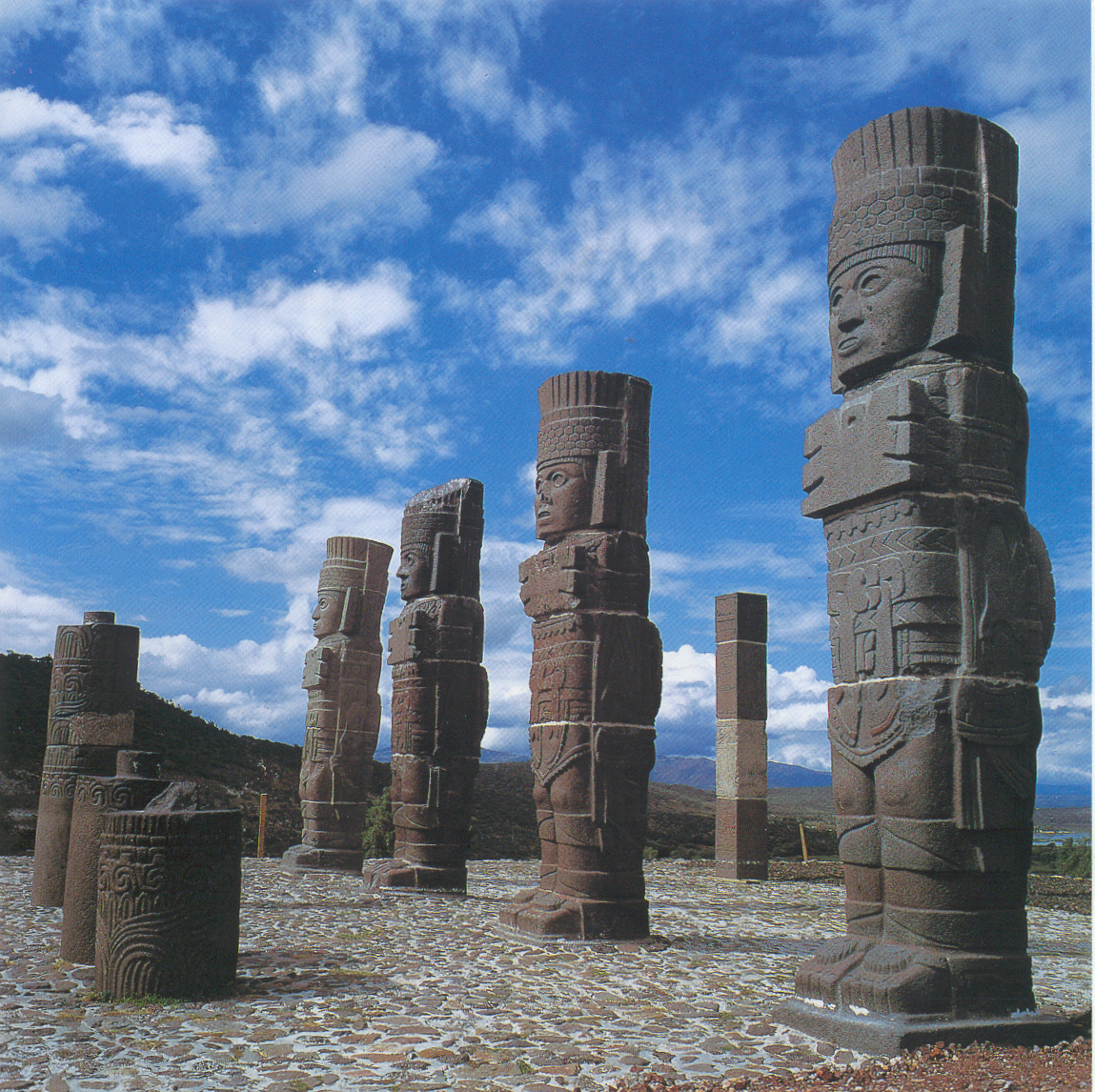

Pyramid B at Tula, also known as the Temple of Quetzalcoatl.

The four basalt warrior columns, also known as atlantes, on top of the Pyramid B at Tula.

To the Aztecs, Teotihuacan was a holy place, where the sun, moon and universe were created. It was they who gave Teotihuacan its name, meaning "The place where men become gods". They also named the Calle de los Muertos, thinking (wrongly) that the many ruined temples and monuments along the "road" were burial places of early rulers. However, the city never regained its concentration of population.

In time earth and grass covered the great pyramids, until they appeared little more than large hills on the landscape. Cortés passed through the area in the 16th century and paid little attention to what structures were visible. It was not until the 19th century that proper excavation and restoration was begun.

The Citadel and Temple of Quetzalcoatl. The main entrance and visitors’ center is directly opposite the La Ciudadela (The Citadel). This large sunken plaza was the city’s administrative center; you’ll see the foundations of several rooms and buildings around the perimeter. Its name was given by the Spanish, who mistook the perimeter platform and pyramid remains for a fortress and towers.

At the eastern end of the plaza, furthest from the visitors’ center, is the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. On approach you will see a four tier pyramid, with steep steps up the nearest side. This construction completely covered a previous pyramid and temple, but excavations on the eastern side have revealed a section of this original building. To see this, walk around the railed platform.

The exposed four-tier (originally six) pyramid has protruding sculptures of serpents alternating with masks of Tlaloc, god of rain and maize. The serpents have plumes or feathers around their necks (Quetzalcoatl being the ‘plumed serpent’) and their bodies curve from the left of the head, ending in a rattle. The Tlaloc masks have corn-cob faces, with big circular eyes and two fangs. Carvings of shells and snails around the masks are earth and water symbols. Originally these would all have been painted in bright colors; green plumes and obsidian eyes for the serpent, white fangs and red jaws for Tlaloc. Some traces of paint can still be seen.

In time earth and grass covered the great pyramids, until they appeared little more than large hills on the landscape. Cortés passed through the area in the 16th century and paid little attention to what structures were visible. It was not until the 19th century that proper excavation and restoration was begun.

The Citadel and Temple of Quetzalcoatl. The main entrance and visitors’ center is directly opposite the La Ciudadela (The Citadel). This large sunken plaza was the city’s administrative center; you’ll see the foundations of several rooms and buildings around the perimeter. Its name was given by the Spanish, who mistook the perimeter platform and pyramid remains for a fortress and towers.

At the eastern end of the plaza, furthest from the visitors’ center, is the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. On approach you will see a four tier pyramid, with steep steps up the nearest side. This construction completely covered a previous pyramid and temple, but excavations on the eastern side have revealed a section of this original building. To see this, walk around the railed platform.

The exposed four-tier (originally six) pyramid has protruding sculptures of serpents alternating with masks of Tlaloc, god of rain and maize. The serpents have plumes or feathers around their necks (Quetzalcoatl being the ‘plumed serpent’) and their bodies curve from the left of the head, ending in a rattle. The Tlaloc masks have corn-cob faces, with big circular eyes and two fangs. Carvings of shells and snails around the masks are earth and water symbols. Originally these would all have been painted in bright colors; green plumes and obsidian eyes for the serpent, white fangs and red jaws for Tlaloc. Some traces of paint can still be seen.

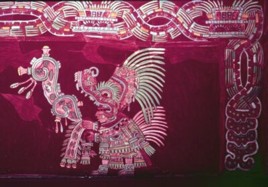

Teotihuacán’s greatest art forms were architecture and mural paintings. Facades of pyramids and interiors of palaces, temples, and homes were frequently decorated with splendid frescoes. The fragment shown here was part of a cycle painted on the interior walls of an aristocratic palace. It shows a rain priest walking or dancing in profile and wearing an elaborate headdress and costume. His speech-scroll, adorned with seashells and plants, indicates that he is praying for water and agricultural prosperity, which were highly valued in his society.

The ancient city of Teotihuacan is the most visited of Mexico’s archaeological sites and a must-see if you’re in Mexico City. The site is impressive for its scale, both in the size of the Pyramid of the Sun (the third largest pyramid in the world) and the majesty of the Calle de los Muertos (Street of the Dead) – originally 4km long and flanked by temples, palaces and platforms Look for amazingly well preserved murals in the Palace of the Jaguars or the Palace of the Quetzal-butterfly and bold sculptures in the Temple of Quetzalcoatl.Teotihuacan ( which acually means “place of those who have the road of the gods”) was, at its height in the first half of the 1st millennium CE (Common Era), the largest city in the Americas. The name Teotihuacan is also used to refer to the civilization that this city was the center of, which at its greatest extent included much of central Mexico. Its influence spread throughout Mesoamerica; evidence of Teotihuacano presence, if not outright political and economic control, can be seen at numerous sites in Veracruz and the Maya region.

Teotihuacan was a large settlement by 150BC, its importance probably arising from a cave system with religious significance, located underneath the present day Pyramid of the Sun. As other settlements in the area diminished, Teotihuacan flourished and became a religious and economic center, controlling the region’s production of obsidian (the black stone used to make weapons and utensils).

Between 1AD and 250AD the ceremonial core was completed, including the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon and the Calle de los Muertos. The massive pyramid structures were painted red and must have been an awe-inspiring sight. Trading relationships were established with Monte Alban in Oaxaca and the gulf coast – there is little evidence of any hostility during the years of prosperity. (You will not see any depictions of warfare or human sacrifice in the carvings and murals at Teotihuacan, unlike many contemporary cities in Mexico).

Major expansion in population and housing occurred between 250-450AD. As many as 200,000 inhabitants have been estimated and at least 2000 “houses” counted. Most of these buildings were home to large family groups or artisan communes. There were even delegations from other cities – a group of craftsmen from Monte Alban is known to have shared a workshop here. The prosperity continued to 650AD and around this time it was the sixth largest city in the world.

In 400AD, with around 200,000 inhabitants Teotihuacan was the sixth largest city in the world – 300 years later it was found virtually abandoned

However, in 650AD, a great fire swept through the city, devastating many communities. For some unknown reason a swift decline ensued and there was no massive reconstruction exercise. Several theories prevail – invasion from a rival city taking advantage of temporary weakness, or a culmination of the erosion of natural resources by over-exploitation.

Whatever the cause, the population soon moved to other growing cities and Teotihuacan was virtually deserted. By the time the Aztecs arrived on the scene, the area was little more than an ancient ruin.

To the Aztecs, Teotihuacan was a holy place, where the sun, moon and universe were created. It was they who gave Teotihuacan its name, meaning “The place where men become gods”. They also named the Calle de los Muertos, thinking (wrongly) that the many ruined temples and monuments along the “road” were burial places of early rulers. However, the city never regained its concentration of population.

The ancient city of Teotihuacan is the most visited of Mexico’s archaeological sites and a must-see if you’re in Mexico City. The site is impressive for its scale, both in the size of the Pyramid of the Sun (the third largest pyramid in the world) and the majesty of the Calle de los Muertos (Street of the Dead) – originally 4km long and flanked by temples, palaces and platforms Look for amazingly well preserved murals in the Palace of the Jaguars or the Palace of the Quetzal-butterfly and bold sculptures in the Temple of Quetzalcoatl.Teotihuacan ( which acually means “place of those who have the road of the gods”) was, at its height in the first half of the 1st millennium CE (Common Era), the largest city in the Americas. The name Teotihuacan is also used to refer to the civilization that this city was the center of, which at its greatest extent included much of central Mexico. Its influence spread throughout Mesoamerica; evidence of Teotihuacano presence, if not outright political and economic control, can be seen at numerous sites in Veracruz and the Maya region.

Teotihuacan was a large settlement by 150BC, its importance probably arising from a cave system with religious significance, located underneath the present day Pyramid of the Sun. As other settlements in the area diminished, Teotihuacan flourished and became a religious and economic center, controlling the region’s production of obsidian (the black stone used to make weapons and utensils).

Between 1AD and 250AD the ceremonial core was completed, including the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon and the Calle de los Muertos. The massive pyramid structures were painted red and must have been an awe-inspiring sight. Trading relationships were established with Monte Alban in Oaxaca and the gulf coast – there is little evidence of any hostility during the years of prosperity. (You will not see any depictions of warfare or human sacrifice in the carvings and murals at Teotihuacan, unlike many contemporary cities in Mexico).

Major expansion in population and housing occurred between 250-450AD. As many as 200,000 inhabitants have been estimated and at least 2000 “houses” counted. Most of these buildings were home to large family groups or artisan communes. There were even delegations from other cities – a group of craftsmen from Monte Alban is known to have shared a workshop here. The prosperity continued to 650AD and around this time it was the sixth largest city in the world.

In 400AD, with around 200,000 inhabitants Teotihuacan was the sixth largest city in the world – 300 years later it was found virtually abandoned

However, in 650AD, a great fire swept through the city, devastating many communities. For some unknown reason a swift decline ensued and there was no massive reconstruction exercise. Several theories prevail – invasion from a rival city taking advantage of temporary weakness, or a culmination of the erosion of natural resources by over-exploitation.

Whatever the cause, the population soon moved to other growing cities and Teotihuacan was virtually deserted. By the time the Aztecs arrived on the scene, the area was little more than an ancient ruin.

To the Aztecs, Teotihuacan was a holy place, where the sun, moon and universe were created. It was they who gave Teotihuacan its name, meaning “The place where men become gods”. They also named the Calle de los Muertos, thinking (wrongly) that the many ruined temples and monuments along the “road” were burial places of early rulers. However, the city never regained its concentration of population.

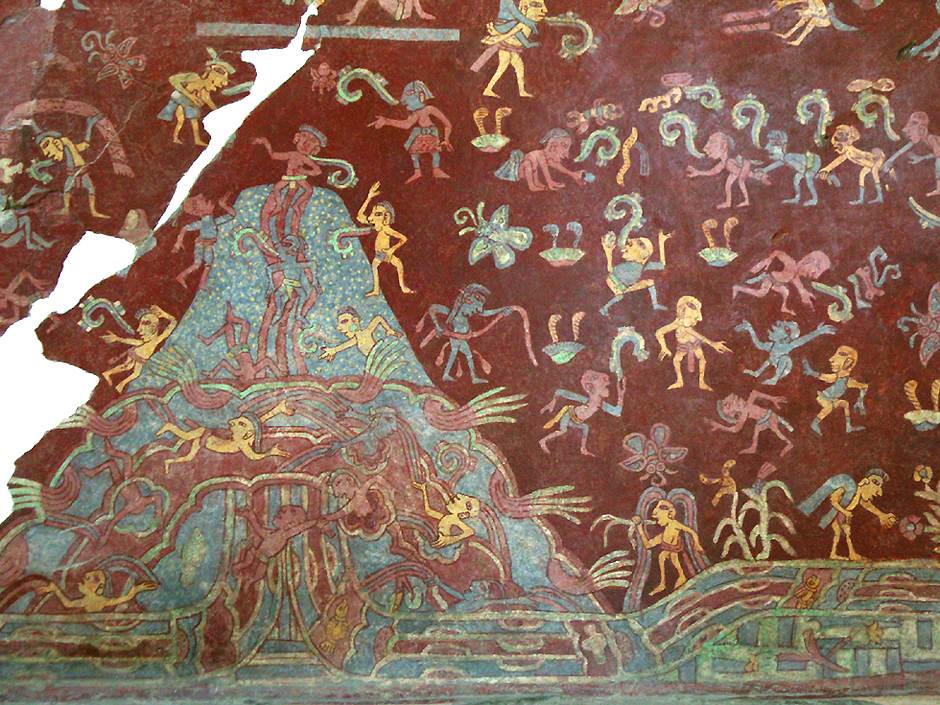

Mural from the Tepantitla compound showing what has been identified as an aspect of the Great Goddess of Teotihuacan, from a reproduction in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.

Actual mural from the Tetitla compound showing a similar portrait.

A portion of the actual mural from the Tepantitla compound which appears under the Great Goddess portrait. There are many interpretations of this scene.

Teotihuacán Eagle Mural

In time earth and grass covered the great pyramids, until they appeared little more than large hills on the landscape. CortÃs passed through the area in the 16th century and paid little attention to what structures were visible. It was not until the 19th century that proper excavation and restoration was begun.

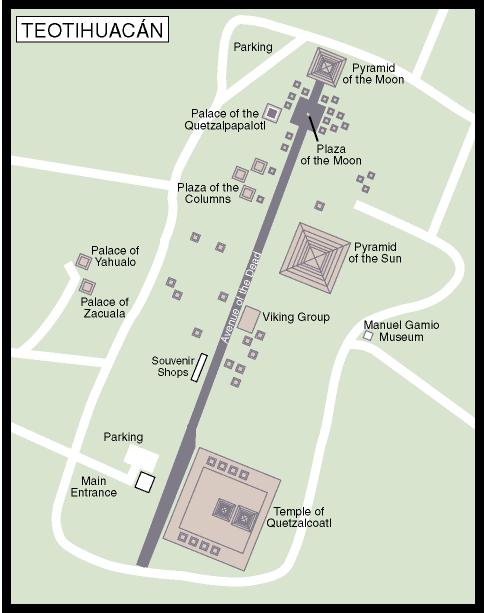

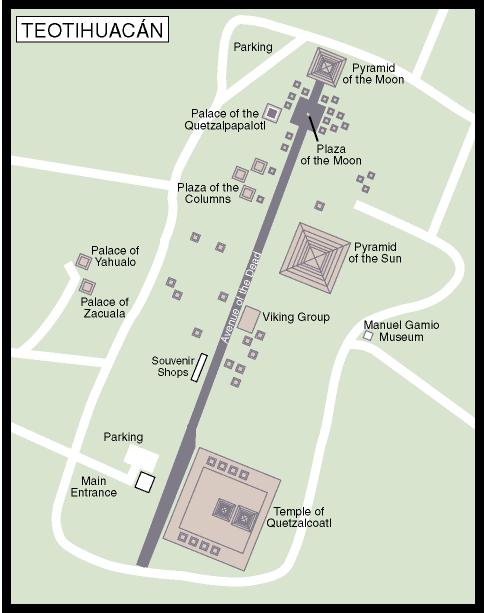

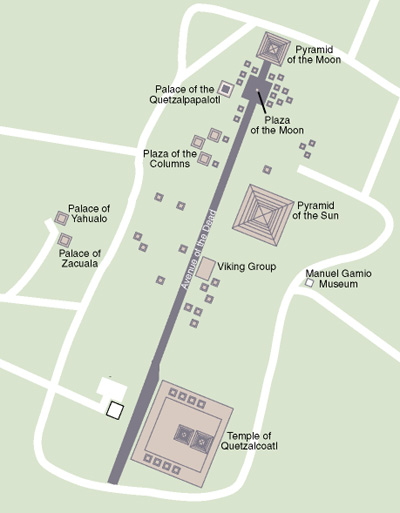

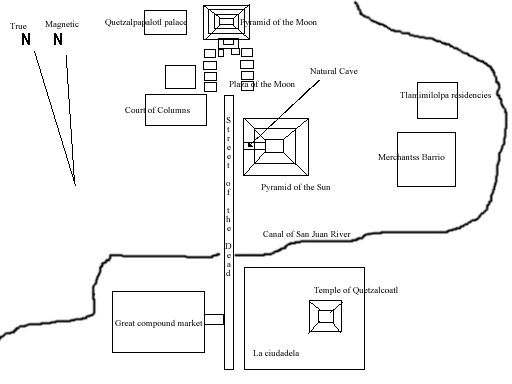

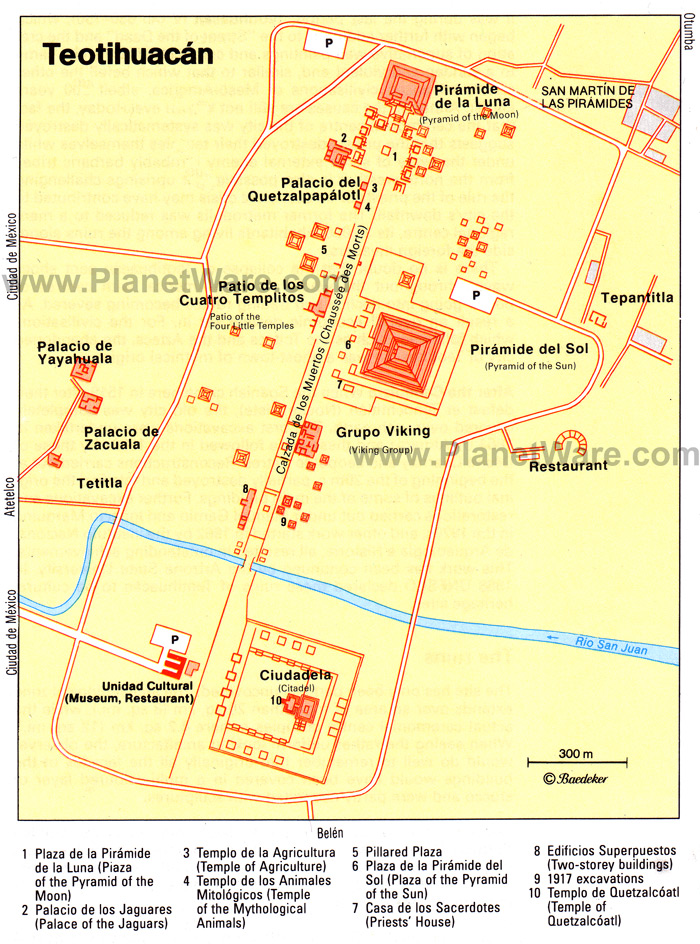

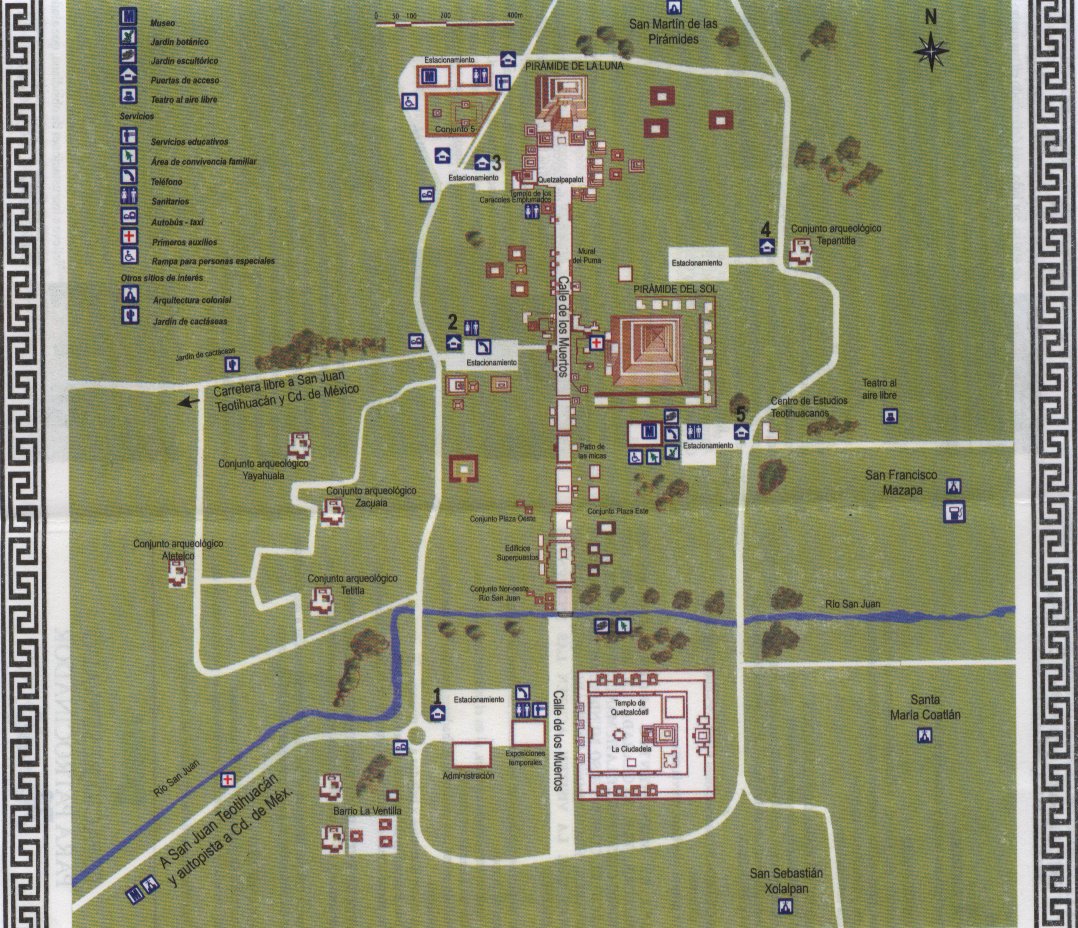

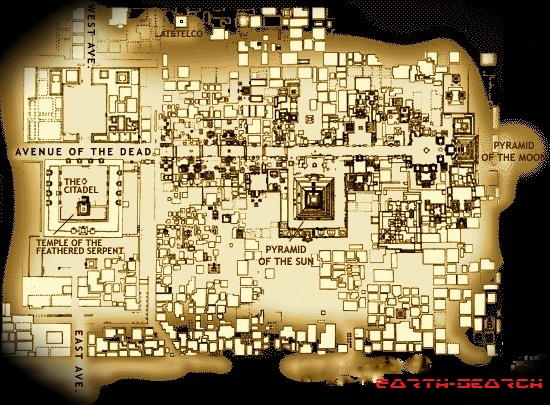

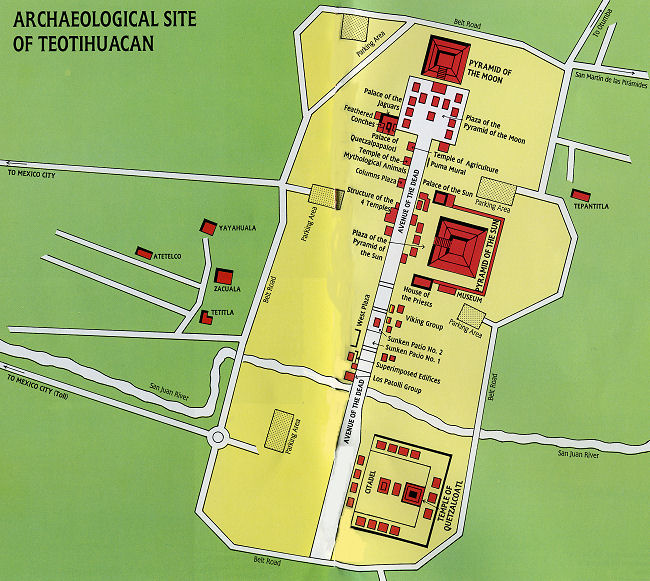

City Layout

The Citadel and Temple of Quetzalcoatl

The main entrance and visitors’ center is directly opposite the La Ciudadela (The Citadel). This large sunken plaza was the city’s administrative center; you’ll see the foundations of several rooms and buildings around the perimeter. Its name was given by the Spanish, who mistook the perimeter platform and pyramid remains for a fortress and towers.

At the eastern end of the plaza, furthest from the visitors’ center, is the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. On approach you will see a four tier pyramid, with steep steps up the nearest side. This construction completely covered a previous pyramid and temple, but excavations on the eastern side have revealed a section of this original building. To see this, walk around the railed platform.

The exposed four-tier (originally six) pyramid has protruding sculptures of serpents alternating with masks of Tláloc, god of rain and maize. The serpents have plumes or feathers around their necks (Quetzalcóatl being the ‘plumed serpent’) and their bodies curve from the left of the head, ending in a rattle. The Tláloc masks have corn-cob faces, with big circular eyes and two fangs. Carvings of shells and snails around the masks are earth and water symbols. Originally these would all have been painted in bright colors; green plumes and obsidian eyes for the serpent, white fangs and red jaws for Tláloc. Some traces of paint can still be seen.

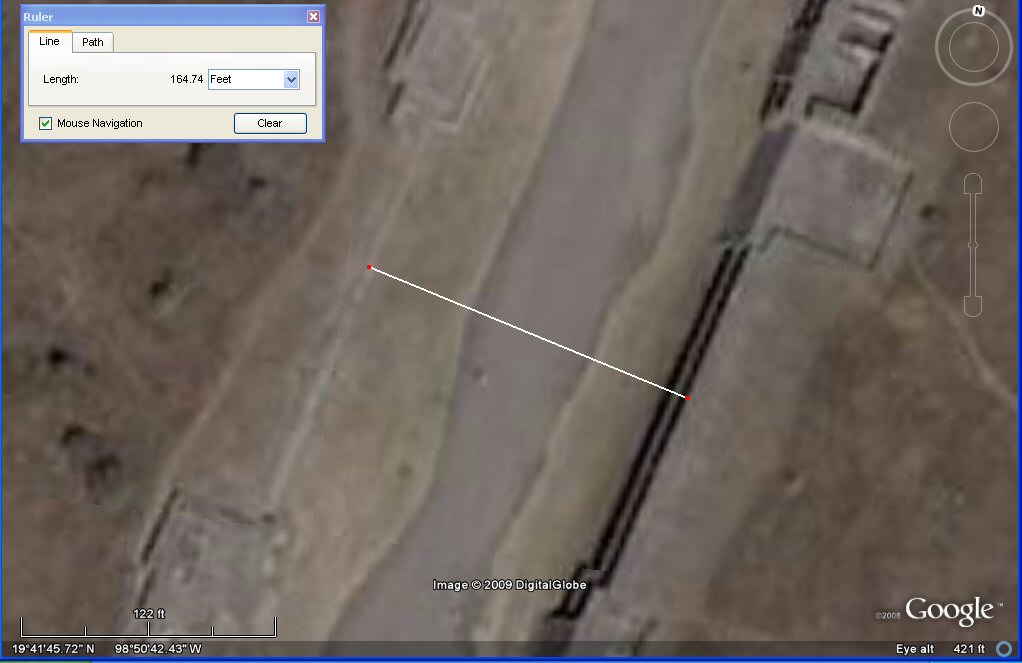

Calle de los Muertos

Leaving the citadel, walk up the Calle de los Muertos towards the Pyramid of the Moon. On the left you’ll pass the “Edificios Superpuestos” (superimposed buildings) where excavations have unearthed living quarters below the present level, filled in with rubble in order to build the second stage.

Pyramid of the Sun

Early reconstruction work by Leopoldo Batres in the early 20th century has unfortunately removed evidence of the true appearance of the pyramid, including its original height. It is now around 215 feet (65 m) high with five tiers, though the fourth and fifth tier were divided by Batres and there were probably only four original, roughly even tiers. Directly under the Pyramid of the Sun is a tunnel which leads to caves used for religious ceremonies

Climb the steps to the top of the pyramid; most of the tiers have small steps that are relatively easier on the legs than those of the Pyramid of the Moon. At the top there would almost certainly have been a temple, of which no trace remains. The view, however, is tremendous and well worth the climb.

Directly under the pyramid is the cave system that is believed to have determined its location. An man-made entrance was discovered in 1971 at the perimeter of the pyramid, with steep stone steps cut into the walls of a shaft 23 feet (7m) deep. From the bottom, a tunnel leads to the natural caves, extended to form four rooms. Here various artifacts were found which indicate early use, probably for religious purposes (caves and water sources, which this was likely to be, were seen as holy places)

The Citadel and Temple of Quetzalcoatl

The main entrance and visitors’ center is directly opposite the La Ciudadela (The Citadel). This large sunken plaza was the city’s administrative center; you’ll see the foundations of several rooms and buildings around the perimeter. Its name was given by the Spanish, who mistook the perimeter platform and pyramid remains for a fortress and towers.

At the eastern end of the plaza, furthest from the visitors’ center, is the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. On approach you will see a four tier pyramid, with steep steps up the nearest side. This construction completely covered a previous pyramid and temple, but excavations on the eastern side have revealed a section of this original building. To see this, walk around the railed platform.

The exposed four-tier (originally six) pyramid has protruding sculptures of serpents alternating with masks of Tláloc, god of rain and maize. The serpents have plumes or feathers around their necks (Quetzalcóatl being the ‘plumed serpent’) and their bodies curve from the left of the head, ending in a rattle. The Tláloc masks have corn-cob faces, with big circular eyes and two fangs. Carvings of shells and snails around the masks are earth and water symbols. Originally these would all have been painted in bright colors; green plumes and obsidian eyes for the serpent, white fangs and red jaws for Tláloc. Some traces of paint can still be seen.

Calle de los Muertos

Leaving the citadel, walk up the Calle de los Muertos towards the Pyramid of the Moon. On the left you’ll pass the “Edificios Superpuestos” (superimposed buildings) where excavations have unearthed living quarters below the present level, filled in with rubble in order to build the second stage.

Pyramid of the Sun

Early reconstruction work by Leopoldo Batres in the early 20th century has unfortunately removed evidence of the true appearance of the pyramid, including its original height. It is now around 215 feet (65 m) high with five tiers, though the fourth and fifth tier were divided by Batres and there were probably only four original, roughly even tiers. Directly under the Pyramid of the Sun is a tunnel which leads to caves used for religious ceremonies

Climb the steps to the top of the pyramid; most of the tiers have small steps that are relatively easier on the legs than those of the Pyramid of the Moon. At the top there would almost certainly have been a temple, of which no trace remains. The view, however, is tremendous and well worth the climb.

Directly under the pyramid is the cave system that is believed to have determined its location. An man-made entrance was discovered in 1971 at the perimeter of the pyramid, with steep stone steps cut into the walls of a shaft 23 feet (7m) deep. From the bottom, a tunnel leads to the natural caves, extended to form four rooms. Here various artifacts were found which indicate early use, probably for religious purposes (caves and water sources, which this was likely to be, were seen as holy places)

Palaces of the Jaguar and Quetzal-butterfly

Approaching the Pyramid of the Moon from the Sun, a grand plaza opens up at the base of the pyramid. Several platforms and smaller pyramids surround the plaza, each pyramid with a central staircase originally leading to a temple.

On the left hand side are the remains of palaces, some with murals and carvings still visible. The Palace of the Jaguar has murals of jaguars with feathered headdresses, whilst in the Palace of the Quetzal-butterfly are carved pillars depicting a hybrid bird-butterfly. The eyes of these creatures were set with obsidian and some still pieces are still intact.

These palaces were elaborately decorated and are assumed to have been the homes of high priests. Other murals can be seen in residential areas outside of the main complex; at Tepantitla behind the Palace of the Sun and also at Tetila and Atetelco, west of the main site.

Teotihaucan Travel Tips

Wear comfortable shoes because Teotihuacan is vast. Even exploring just the highlights requires substantial walking.

Another physical exertion: The high altitude can make step climbing fatiguing.

Summer middays can be sweltering, so come early or late to avoid the heat (and crowds).

Early is preferable to late because thunderstorms occur more frequently in the afternoon.

In the wintertime, the temperature can become nippy and a bit raw.

Teotihuacan is best photographed in the early morning and late afternoon light (for contrasting shadows).

The population estimates of Teotihuacan in its glory days generally range between 75,000 to 200,000. Those figures would make it one of the world’s largest cities in its time.

After its prime time (from around 200 BC to 350 AD), Teotihuacan slowly deteriorated physically and in spirit over the next several centuries, then died.

The Teotihuacan moniker was coined by the invading Aztecs, relative newbies. They did not take possession of the complex until a relatively short time before Cortez invaded Mexico in the 16th century. That was nearly a millennium after the original builders abandoned their religious and commercial center.

The Aztecs used the top of the Pyramid of the Sun as an altar for sacrificing captives of war to the solar god. The hapless souls were marched huffing and puffing up the 247 steep steps to have their hearts ceremoniously ripped out by a priest and their heartless bodies unceremoniously tossed down the sheer sides of the Pyramid of the Sun.

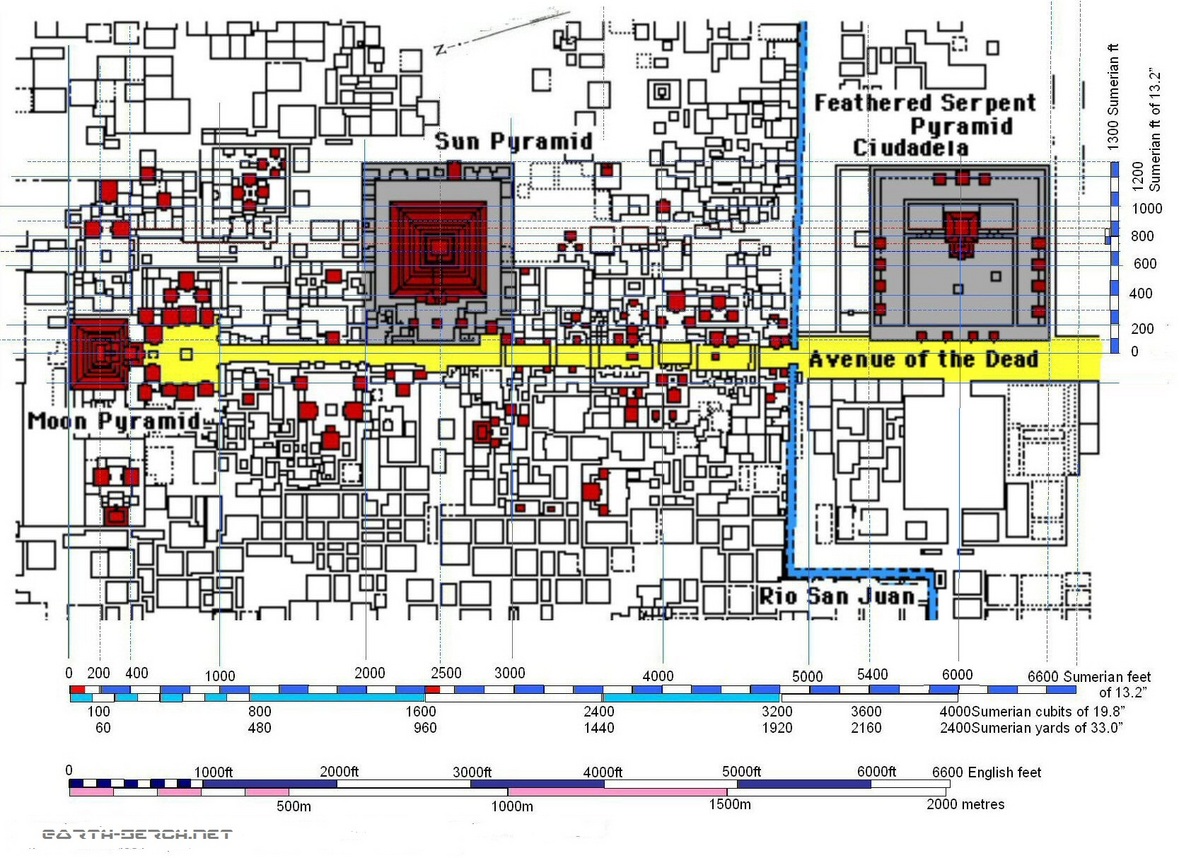

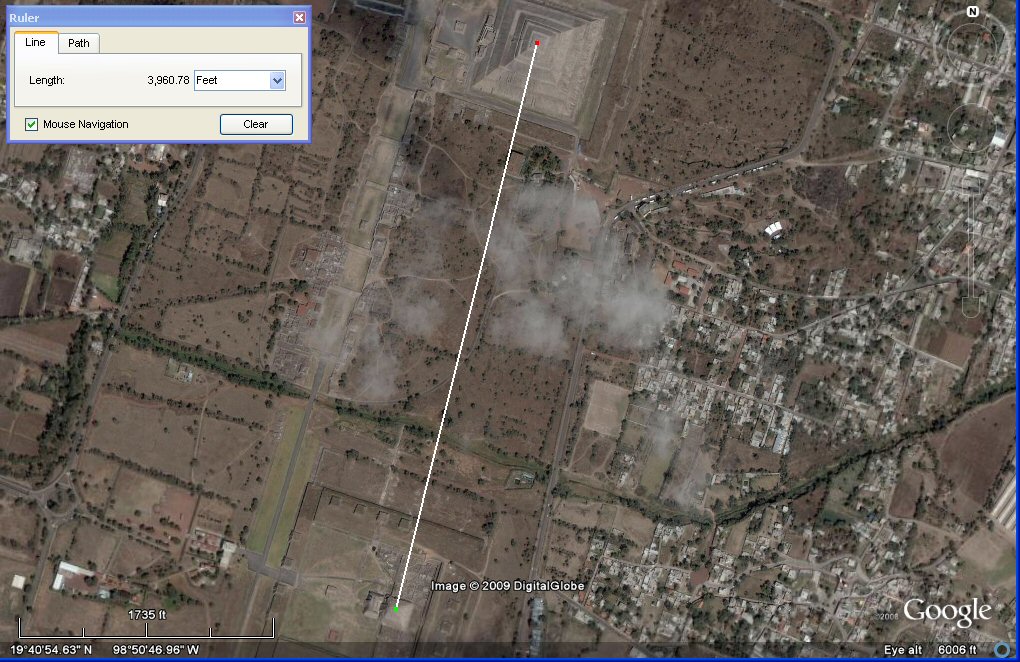

The Avenue of the Dead was the main street of Teotihuacan. It ran for more than 2.5 km, beginning at the Moon Plaza to the north and extending beyond the Ciudadela and the Great Compound complexes to the south.

The avenue divided the city into two sections. Apartment compounds with pyramidal constructions were arranged on both sides of the avenue, often symetrically and sharing the same orientation. This highly planned city-layout suggests that the avenue may have been planned since its earliest phases of urbanization.

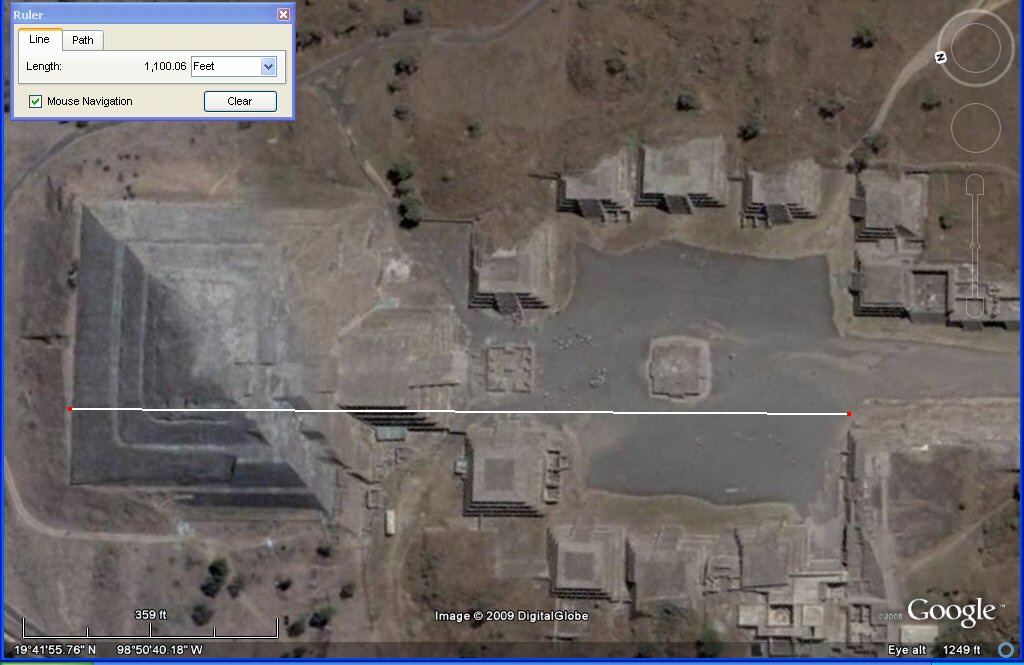

As originally built, the Sun Pyramid was approximately 215 by 215 m at the base, and about 63 m high. It was significantly enlarged at least twice in later periods, resulting in a final size of 225 m along each side. The pyramid was located on the east side of the Avenue of the Dead in the northern half of the city. If the area of monumental construction between the Moon Pyramid and the San Juan Canal is regarded as the central zone of the city, the Sun Pyramid is located at its middle. In addition to its geographic centrality, the importance of the pyramid is indicated by a cave located under the structure. It is believed by certain scholars that the cave was used for ritual activities, and why the pyramid was constructed where it is today.

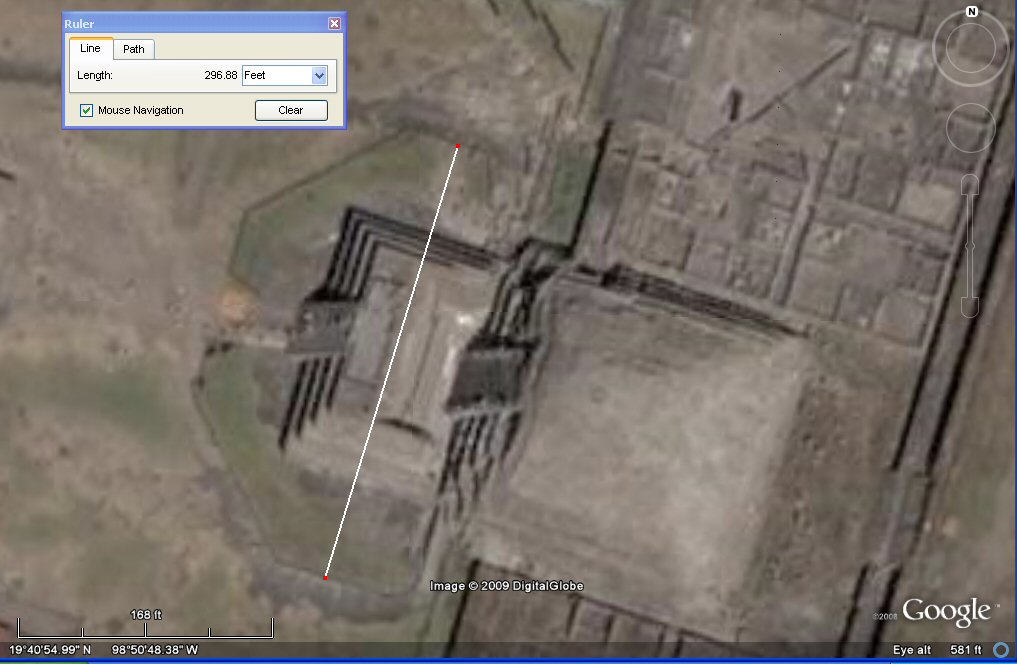

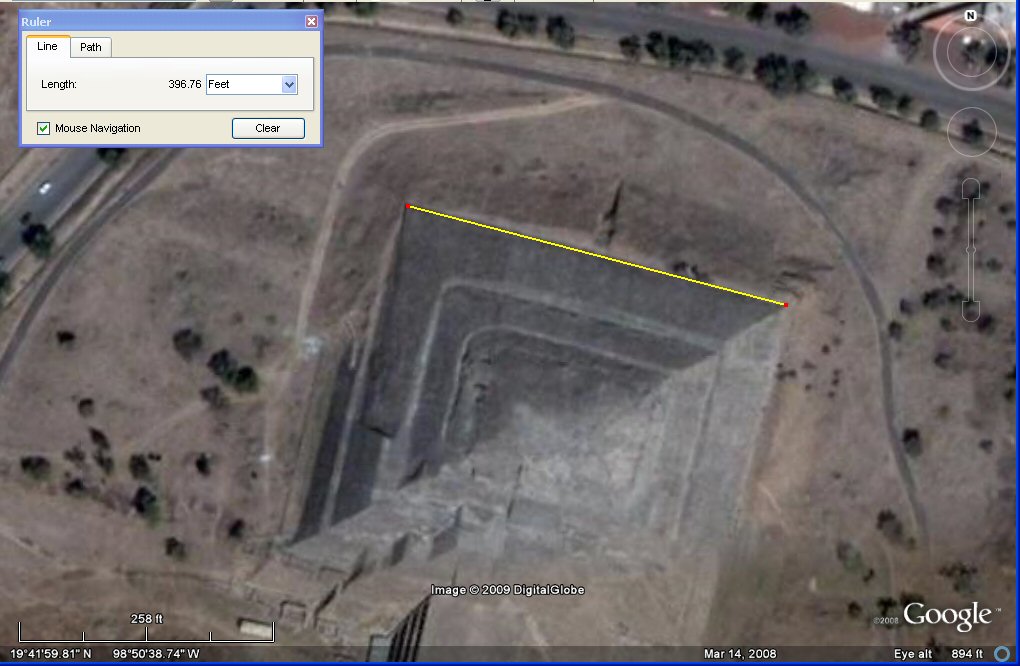

The Ciudadela is a huge enclosure located at the geographic center of the city. It measures about 400 m on a side (i.e. about 160,000 m2), and the interior space is surrounded by four large platforms surmounted by pyramids. The main plaza had a capacity of about 100,000 persons without much crowding. One of the main functions of this closed huge space may have been ritual performance.

(Information from the University of Arizona)

Approaching the Pyramid of the Moon from the Sun, a grand plaza opens up at the base of the pyramid. Several platforms and smaller pyramids surround the plaza, each pyramid with a central staircase originally leading to a temple.

On the left hand side are the remains of palaces, some with murals and carvings still visible. The Palace of the Jaguar has murals of jaguars with feathered headdresses, whilst in the Palace of the Quetzal-butterfly are carved pillars depicting a hybrid bird-butterfly. The eyes of these creatures were set with obsidian and some still pieces are still intact.

These palaces were elaborately decorated and are assumed to have been the homes of high priests. Other murals can be seen in residential areas outside of the main complex; at Tepantitla behind the Palace of the Sun and also at Tetila and Atetelco, west of the main site.

Teotihaucan Travel Tips

Wear comfortable shoes because Teotihuacan is vast. Even exploring just the highlights requires substantial walking.

Another physical exertion: The high altitude can make step climbing fatiguing.

Summer middays can be sweltering, so come early or late to avoid the heat (and crowds).

Early is preferable to late because thunderstorms occur more frequently in the afternoon.

In the wintertime, the temperature can become nippy and a bit raw.

Teotihuacan is best photographed in the early morning and late afternoon light (for contrasting shadows).

The population estimates of Teotihuacan in its glory days generally range between 75,000 to 200,000. Those figures would make it one of the world’s largest cities in its time.

After its prime time (from around 200 BC to 350 AD), Teotihuacan slowly deteriorated physically and in spirit over the next several centuries, then died.

The Teotihuacan moniker was coined by the invading Aztecs, relative newbies. They did not take possession of the complex until a relatively short time before Cortez invaded Mexico in the 16th century. That was nearly a millennium after the original builders abandoned their religious and commercial center.

The Aztecs used the top of the Pyramid of the Sun as an altar for sacrificing captives of war to the solar god. The hapless souls were marched huffing and puffing up the 247 steep steps to have their hearts ceremoniously ripped out by a priest and their heartless bodies unceremoniously tossed down the sheer sides of the Pyramid of the Sun.

The Avenue of the Dead was the main street of Teotihuacan. It ran for more than 2.5 km, beginning at the Moon Plaza to the north and extending beyond the Ciudadela and the Great Compound complexes to the south.

The avenue divided the city into two sections. Apartment compounds with pyramidal constructions were arranged on both sides of the avenue, often symetrically and sharing the same orientation. This highly planned city-layout suggests that the avenue may have been planned since its earliest phases of urbanization.

As originally built, the Sun Pyramid was approximately 215 by 215 m at the base, and about 63 m high. It was significantly enlarged at least twice in later periods, resulting in a final size of 225 m along each side. The pyramid was located on the east side of the Avenue of the Dead in the northern half of the city. If the area of monumental construction between the Moon Pyramid and the San Juan Canal is regarded as the central zone of the city, the Sun Pyramid is located at its middle. In addition to its geographic centrality, the importance of the pyramid is indicated by a cave located under the structure. It is believed by certain scholars that the cave was used for ritual activities, and why the pyramid was constructed where it is today.

The Ciudadela is a huge enclosure located at the geographic center of the city. It measures about 400 m on a side (i.e. about 160,000 m2), and the interior space is surrounded by four large platforms surmounted by pyramids. The main plaza had a capacity of about 100,000 persons without much crowding. One of the main functions of this closed huge space may have been ritual performance.

(Information from the University of Arizona)

Approaching the major temple sites

The Temple of the Feathered Serpent has a facade with a series of repeating images

Feaethered serpents are the most prominent images on the facade

In some cases, one can still see the remnants of the white paint that was used to emphasize the teeth

In one of the rooms beside the Luna temple is a preserved mural of a jaguar

In addition to the feathered serpent, the reliefs depict marine snails and an apple snail from fresh water

This is the location of the central living areas where about 100,000 people lived.

On top of the rooms, there are courtyards that may be upper story rooms.

The largest of the temples is dedicated to the sun and called Sol.

The smaller of the two temples is dedicated to the moon and is called Luna.

On this temple, the stairs are very steep and at frequent intervals there are facades possibly originally with murals.

From the top of Luna, one can see the full extent of the plaza and the view of Sol in the distance.

Teotihuacán,

View of the Avenue of the Dead (center) and Pyramid of the Sun (left)

from the Temple of the Moon, Teotihuacán.

from the Temple of the Moon, Teotihuacán.

Teotihuacán ("teh-oh-tee-wa-KHAN") is an ancient sacred site located 30 miles northeast of Mexico City, Mexico. It is a very popular side trip from Mexico City, and for good reason. The ruins of Teotihuacán are among the most remarkable in Mexico and some of the most important ruins in the world.

Teotihuacán means "place where gods were born," reflecting the Aztec belief that the gods created the universe here. Constructed around 300 AD, the holy city is characterized by the vast size of its monuments, carefully laid out on geometric and symbolic principles. Its most monumental structures are the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, the Pyramid of the Sun (the third-largest pyramid in the world) and the Pyramid of the Moon.

Teotihuacán means "place where gods were born," reflecting the Aztec belief that the gods created the universe here. Constructed around 300 AD, the holy city is characterized by the vast size of its monuments, carefully laid out on geometric and symbolic principles. Its most monumental structures are the Temple of Quetzalcoatl, the Pyramid of the Sun (the third-largest pyramid in the world) and the Pyramid of the Moon.

The early history of Teotihuacán is shrouded in mystery. Little is known about its ancient builders, including their name, precise religious beliefs, or language. The city became the epicenter of culture and commerce for ancient Mesoamerica, surpassing Rome in size, yet its inhabitants suddenly abandoned it for unknown reasons.

People first moved to the area around 500 BC. Sometime after 100 BC, construction of the enormous Pyramid of the Sun commenced. Teotihuacán's rise thus coincided with that of classical Rome, and with the beginning of cultures in Mexico's Yucatán Peninsula, Oaxaca, and Puebla.

At its zenith around 500 AD, Teotihuacán's magnificent pyramids and palaces covered 12 square miles (31 sq km) and the city was larger in size and population than Rome. Through trade and other contact, Teotihuacán's influence was felt as far south as the Yucatán and Guatemala.

Teotihuacános were formidable warriors and that their aim in warfare was not conquest of territory but the capture of prisoners who were sacrificed to avert the end of the world.

According to the mythology shared by most ancient peoples of Central America, the world had undergone four cycles or "suns." They lived in the fifth sun, which was already old. Thus they expected the end of the world at any moment, which was expected to happen by earthquakes.

In an effort to postpone this cataclysmic event, humans were sacrificed by the thousands. Humans also seem to have been sacrificed to dedicate a new or expanded building. In the Pyramid of the Sun, the corner of each step contained skeletons of children. Discovered below the Temple of Quetzalcoatl were three burial pits full of skeletons.

According to the mythology shared by most ancient peoples of Central America, the world had undergone four cycles or "suns." They lived in the fifth sun, which was already old. Thus they expected the end of the world at any moment, which was expected to happen by earthquakes.

In an effort to postpone this cataclysmic event, humans were sacrificed by the thousands. Humans also seem to have been sacrificed to dedicate a new or expanded building. In the Pyramid of the Sun, the corner of each step contained skeletons of children. Discovered below the Temple of Quetzalcoatl were three burial pits full of skeletons.

Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent withgods Tlaloc and Quetzalcoatl.

It appears that the primary deity at Teotihuacán was a female, called the "Spider Woman" by scholars. There are also depictions of other female deities, including a Water Goddess. According to archaeoastronomer John B. Carlson, the cult of the planet Venus that determined wars and human sacrifices elsewhere in Mesoamerica was prominent at Teotihuacán as well. Ceremonial rituals were timed with the appearance of Venus as the morning and evening star. The symbol of Venus at Teotihuacán appears as a star or half star with a full or half circle.

Other important deities at Teotihuacán included: the Rain God (called Tlaloc by the Aztecs); Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent; the Sun God and Moon Goddess; and Xipe Totec (Our Lord the Flayed One, associated with renewed vegetation). Incense burners have been found related to the Old Fire God, a creator divinity possibly associated with the Spider Woman.

For reasons that are not known for certain, the inhabitants of Teotihuacán gradually abandoned their great city around 700 AD. Scholars believe the decline was probably caused by overpopulation and depletion of natural resources.

About 50 years after its abandonment, Teotihuacán was destroyed by fire, leaving some of its greatest monuments buried under millions of tons of earth. It is possible that the city was deliberately burned by its former inhabitants, or by invaders that regarded the religion of Teotihuacán as a false one - the Toltecs have been suggested as possible culprits.

Other important deities at Teotihuacán included: the Rain God (called Tlaloc by the Aztecs); Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent; the Sun God and Moon Goddess; and Xipe Totec (Our Lord the Flayed One, associated with renewed vegetation). Incense burners have been found related to the Old Fire God, a creator divinity possibly associated with the Spider Woman.

For reasons that are not known for certain, the inhabitants of Teotihuacán gradually abandoned their great city around 700 AD. Scholars believe the decline was probably caused by overpopulation and depletion of natural resources.

About 50 years after its abandonment, Teotihuacán was destroyed by fire, leaving some of its greatest monuments buried under millions of tons of earth. It is possible that the city was deliberately burned by its former inhabitants, or by invaders that regarded the religion of Teotihuacán as a false one - the Toltecs have been suggested as possible culprits.

Quetzalcoatl and Tlaloc

It was the Aztecs who gave Teotihuacán its name, when they arrived here in about 1320. The name means "City of Gods," and they believed the gods had gathered here to create the sun and moon after the last world ended. Teotihuacán was highly revered by the Aztecs and used as a pilgrimage center from their base in Tenochtitlán, modern Mexico City.

Already astonished at the size and sophistication of Mexico City (Tenochtitlán), we can only imagine the reaction of Fernando Cortes and his men when they stumbled upon the great ceremonial center of Teotihuacán in 1520. Legend has it that one of the reasons the Aztecs were defeated so quickly by the outnumbered Spaniards was that they mistook him for Quetzalcoatl, who was expected to arrive from the Atlantic in the form of a bearded white man.

What to See

Today, what remains are the rough stone structures of the three pyramids and sacrificial altars, and some of the grand houses, all of which were once covered in stucco and painted with brilliant frescoes (mainly in red).

Already astonished at the size and sophistication of Mexico City (Tenochtitlán), we can only imagine the reaction of Fernando Cortes and his men when they stumbled upon the great ceremonial center of Teotihuacán in 1520. Legend has it that one of the reasons the Aztecs were defeated so quickly by the outnumbered Spaniards was that they mistook him for Quetzalcoatl, who was expected to arrive from the Atlantic in the form of a bearded white man.

What to See

Today, what remains are the rough stone structures of the three pyramids and sacrificial altars, and some of the grand houses, all of which were once covered in stucco and painted with brilliant frescoes (mainly in red).

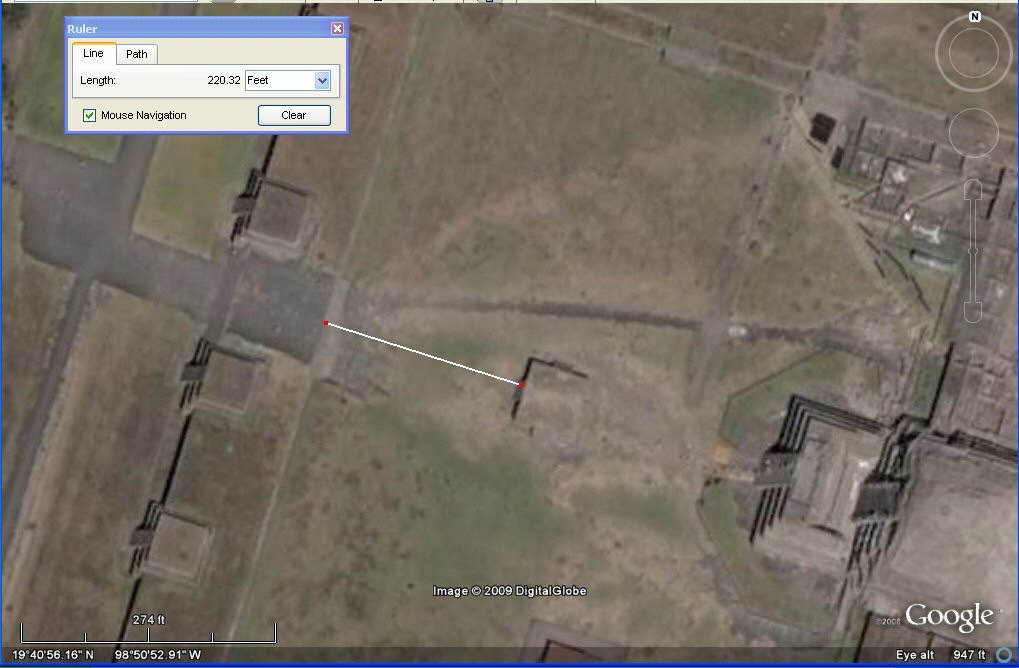

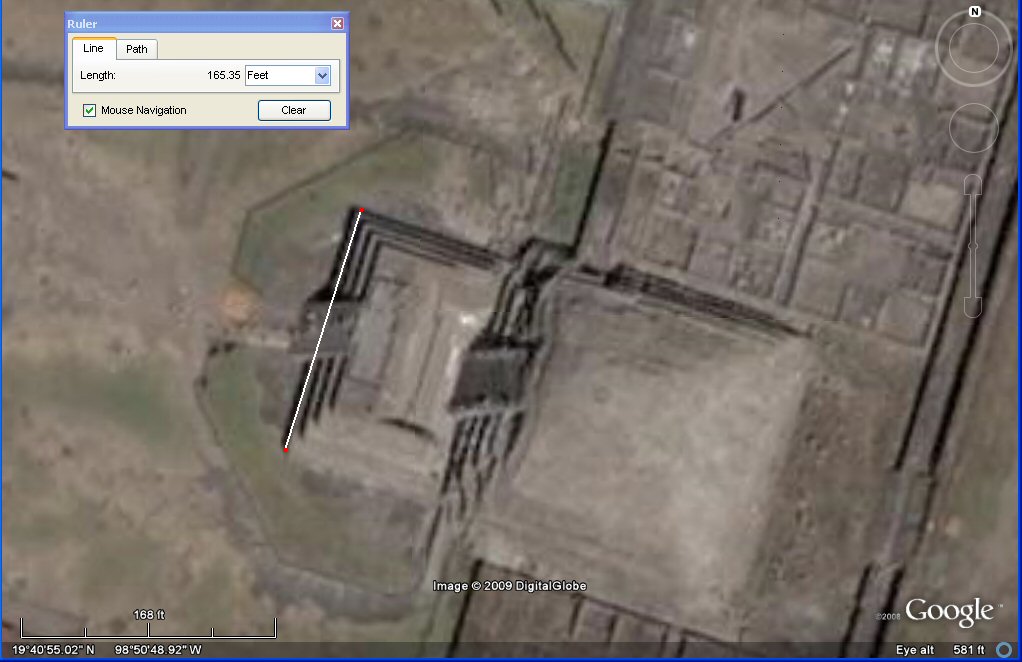

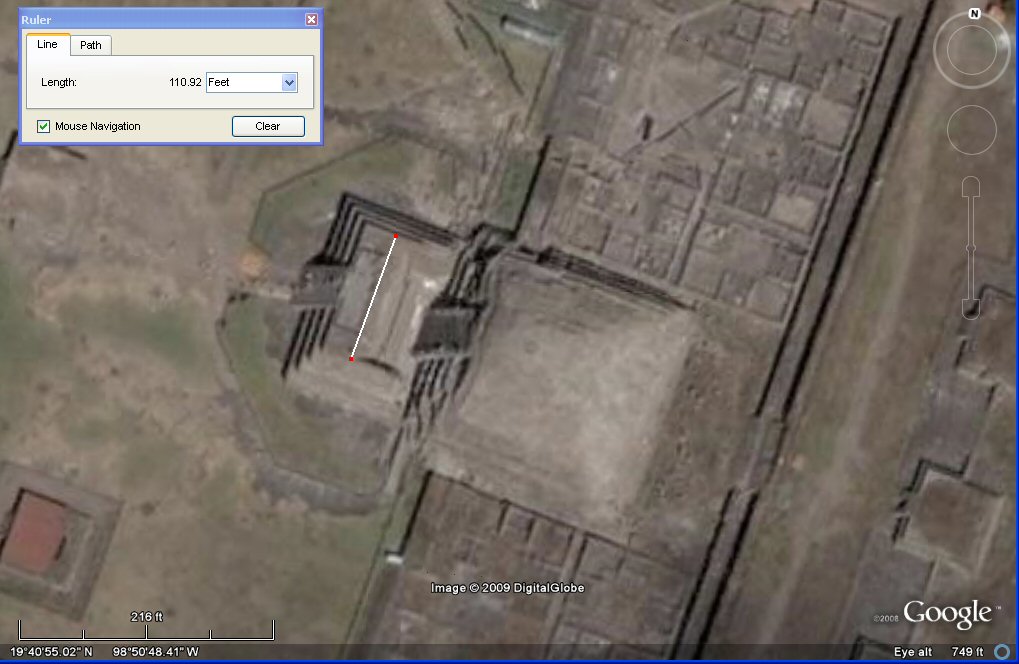

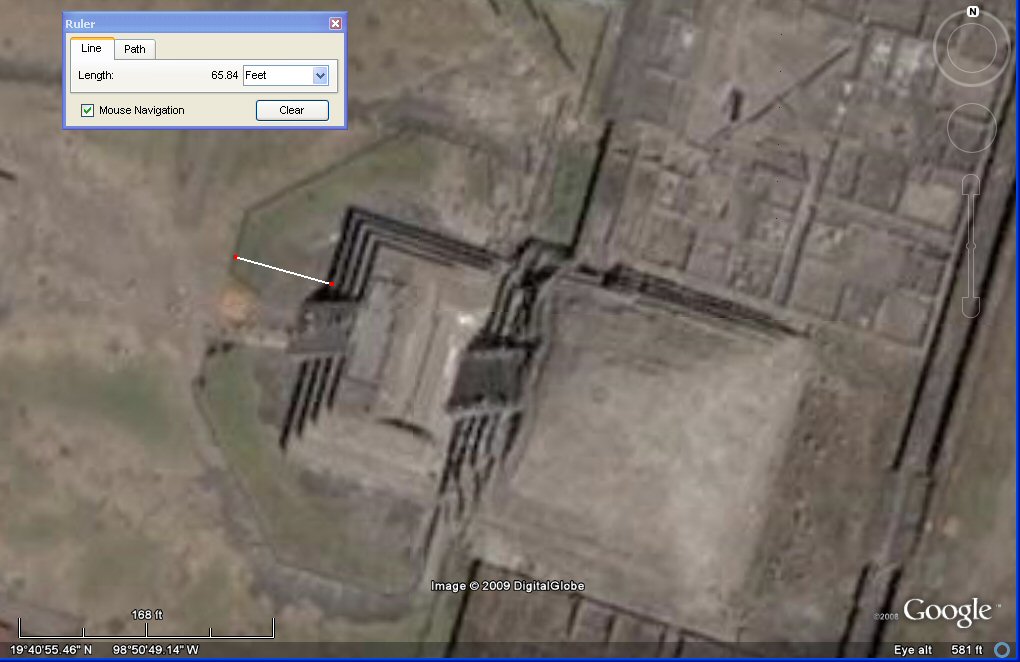

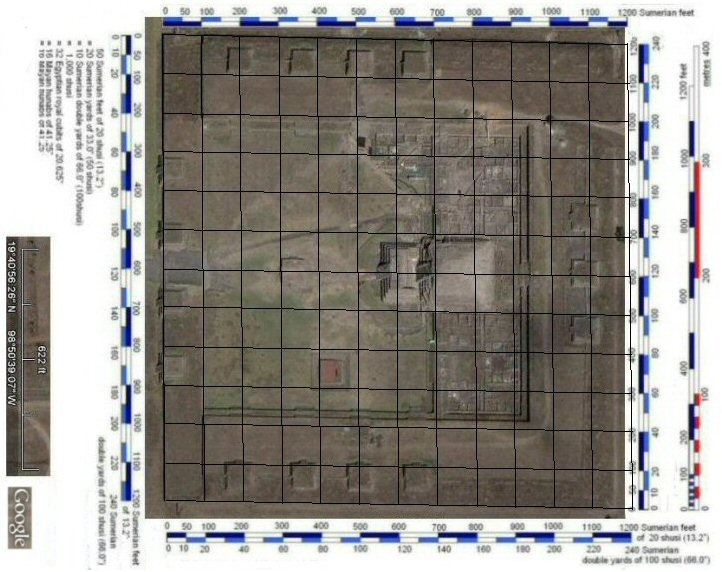

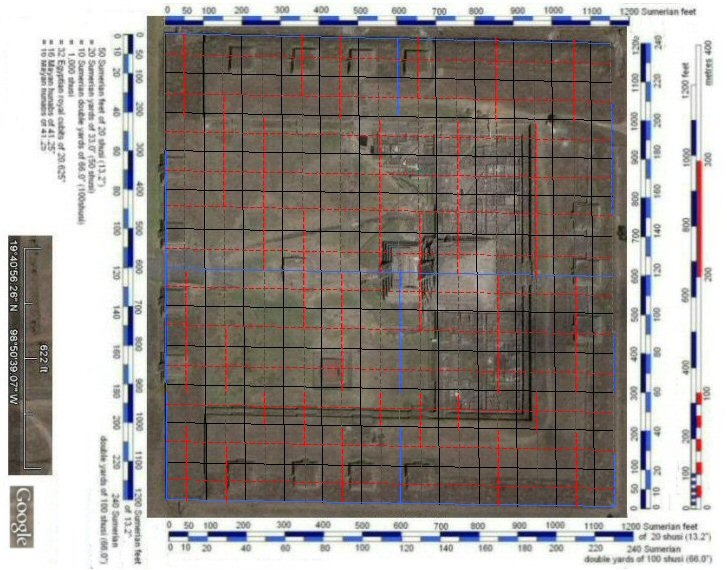

Aerial view of Teotihuacán, oriented north. The Pyramid of the Moon is

at the top; the larger Pyramid of the Sun on the bottom. See below for

an interactive view. Image © Google Earth

at the top; the larger Pyramid of the Sun on the bottom. See below for

an interactive view. Image © Google Earth

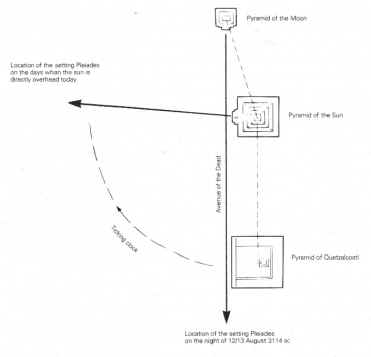

The whole city of Teotihuacán seems to be aligned astronomically. It is consistently oriented 15 to 25 degrees east of true north, and the front wall of the Pyramid of the Sun is exactly perpendicular to the point on the horizon where the sun sets on the equinoxes. The rest of the ceremonial buildings were laid out at right angles to the Pyramid of the Sun. The Avenue of the Dead points at the setting of the Pleiades. Another alignment is to the dog star Sirius, sacred to the ancient Egyptians, which has led some to suggest a link between the great pyramids of Egypt and Mexico.

The main thoroughfare, which archaeologists call the Avenue of the Dead (Calzada de los Muertos), runs two miles roughly north to south. The Pyramid of the Moon is at the northern end, and the Citadel (Ciudadela) is on the southern part. It was once thought that the Avenue ended with the Citadel, but it is now known that is actually twice the length and the city was divided into quarters.

The great street was several kilometers long in its prime, but only a kilometer or two has been uncovered and restored. The Avenue of the Dead got its forbidding name from the Aztecs, who wrongly believed the little temples on either side of the avenue were tombs.

The main thoroughfare, which archaeologists call the Avenue of the Dead (Calzada de los Muertos), runs two miles roughly north to south. The Pyramid of the Moon is at the northern end, and the Citadel (Ciudadela) is on the southern part. It was once thought that the Avenue ended with the Citadel, but it is now known that is actually twice the length and the city was divided into quarters.

The great street was several kilometers long in its prime, but only a kilometer or two has been uncovered and restored. The Avenue of the Dead got its forbidding name from the Aztecs, who wrongly believed the little temples on either side of the avenue were tombs.

Temples line the Avenue of the Dead

As you stroll north along the Avenue toward the Pyramid of the Moon, look on the right for a bit of wall sheltered by a modern corrugated roof. Beneath the shelter, the wall still bears a painting of a jaguar. Imagine the breathtaking spectacle the Avenue must have been when all the paintings were intact!

The Spaniards named the Ciudadela, or Citadel, at the southern end of the Avenue of the Dead. This immense sunken square was not a fortress at all, despite its impressive walls. Rather, it was the grand setting for the Feathered Serpent Pyramid and the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. The feathered serpent is featured in the Ciudadela, but whether it was worshipped as Quetzalcoatl or a similar god isn't known for certain.

The Temple of Quetzalcoatl is not nearly as large as the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon, but instead it enjoys a central location, lavish offerings and fine decoration. The facade of the temple features fine, large carved serpents' heads jutting out from collars of feathers carved in the stone walls; these weigh 4 tons. Other feathered serpents are carved in relief low on the walls.

The Spaniards named the Ciudadela, or Citadel, at the southern end of the Avenue of the Dead. This immense sunken square was not a fortress at all, despite its impressive walls. Rather, it was the grand setting for the Feathered Serpent Pyramid and the Temple of Quetzalcoatl. The feathered serpent is featured in the Ciudadela, but whether it was worshipped as Quetzalcoatl or a similar god isn't known for certain.

The Temple of Quetzalcoatl is not nearly as large as the Pyramids of the Sun and Moon, but instead it enjoys a central location, lavish offerings and fine decoration. The facade of the temple features fine, large carved serpents' heads jutting out from collars of feathers carved in the stone walls; these weigh 4 tons. Other feathered serpents are carved in relief low on the walls.

The Temple of Quetzalcoatl is topped with a pyramid, known as the Feathered Serpent Pyramid. Archaeologists have tunneled deep inside the Feathered Serpent Pyramid and found more than 200 ceremonially buried skeletons of warriors, interred with precise detail and position. In addition, a single slain captive was placed at each of the pyramid's four corners.

The Pyramid of the Sun, on the east side of the Avenue of the Dead, is the third-largest pyramid in the world (surpassed only by the Great Pyramid of Cholula and the Great Pyramid of Cheops in Egypt). It is the biggest restored pyramid in the Western Hemisphere and an awesome sight.

The purpose of the Pyramid of the Sun is not entirely understood, but it is built on top of a sacred cave shaped like a four-leafed clover. Given the grand pyramid above, this cave was probably regarded as the very place where the gods created the world. The cave is not open to the public.

The Pyramid of the Sun, on the east side of the Avenue of the Dead, is the third-largest pyramid in the world (surpassed only by the Great Pyramid of Cholula and the Great Pyramid of Cheops in Egypt). It is the biggest restored pyramid in the Western Hemisphere and an awesome sight.

The purpose of the Pyramid of the Sun is not entirely understood, but it is built on top of a sacred cave shaped like a four-leafed clover. Given the grand pyramid above, this cave was probably regarded as the very place where the gods created the world. The cave is not open to the public.

Jaguar mural, Avenue of the Dead.

Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent (Alexandre Bourdeu); crowds atop

the Pyramid of the Sun (Murat Arslanoglu

the Pyramid of the Sun (Murat Arslanoglu

The first part of the Pyramid of the Sun was probably built around 100 BC, and the temple that used to crown the pyramid was completed about 400 years later (300 AD). By the time the pyramid was discovered and restoration was begun in the 20th century, the temple had disappeared, and the pyramid was just a mass of rubble covered with bushes and trees. It's a worthwhile 248-step climb to the top. The view is extraordinary and the sensation exhilarating.

The on-site Museo Teotihuacán is a good place to start a visit. This state-of-the-art museum features interactive exhibits and a glass floor on which visitors walk above models of the pyramids. On display are findings of recent digs, including several tombs, with skeletons wearing necklaces of human and simulated jawbones, and newly-discovered sculptures.

Keep in mind that Teotihuacán is located at an altitude of more than 7,000 feet (2,121m). Take it slow, bring sunblock and water, and be prepared for almost daily afternoon showers in the summer.

Vendors at the site sell drinks and snacks, but many visitors choose to bring a picnic lunch, which almost any hotel or restaurant in the city will prepare. There is also a restaurant in the Museo Teotihuacán.

Keep in mind that Teotihuacán is located at an altitude of more than 7,000 feet (2,121m). Take it slow, bring sunblock and water, and be prepared for almost daily afternoon showers in the summer.

Vendors at the site sell drinks and snacks, but many visitors choose to bring a picnic lunch, which almost any hotel or restaurant in the city will prepare. There is also a restaurant in the Museo Teotihuacán.

The Pyramid of the Moon from atop the Pyramid of the Sun.

Getting There

Driving to San Juan Teotihuacán on the toll Highway 85D or the free Highway 132D takes about an hour. Head north on Insurgentes to leave the city. Highway 132D passes through picturesque villages but can be slow due to the surfeit of trucks and buses. Highway 85D, the toll road, is less attractive but faster.

If you prefer to explore solo or want more or less time than an organized tour allows, consider hiring a private car and driver for the trip. They can easily be arranged through your hotel or at the Secretary of Tourism (SECTUR) information module in the Zona Rosa; they cost about $10 to $15 an hour. The higher price is generally for a sedan with an English-speaking driver who doubles as a tour guide. Rates can also be negotiated for the entire day.

Buses leave daily every half hour (5am-10pm) from the Terminal Central de Autobuses del Norte; the trip takes 1 hour. When you reach the Terminal Norte, look for the AUTOBUSES SAHAGUN sign at the far northwest end, all the way down to the sign 8 ESPERA. Be sure to ask the driver where you should wait for returning buses, how frequently buses run, and especially the time of the last bus back.

A small trolley-train that takes visitors from the entry booths to various stops within the site, including the Teotihuacán museum and cultural center, runs only on weekends and costs 60¢ per person.

Driving to San Juan Teotihuacán on the toll Highway 85D or the free Highway 132D takes about an hour. Head north on Insurgentes to leave the city. Highway 132D passes through picturesque villages but can be slow due to the surfeit of trucks and buses. Highway 85D, the toll road, is less attractive but faster.

If you prefer to explore solo or want more or less time than an organized tour allows, consider hiring a private car and driver for the trip. They can easily be arranged through your hotel or at the Secretary of Tourism (SECTUR) information module in the Zona Rosa; they cost about $10 to $15 an hour. The higher price is generally for a sedan with an English-speaking driver who doubles as a tour guide. Rates can also be negotiated for the entire day.

Buses leave daily every half hour (5am-10pm) from the Terminal Central de Autobuses del Norte; the trip takes 1 hour. When you reach the Terminal Norte, look for the AUTOBUSES SAHAGUN sign at the far northwest end, all the way down to the sign 8 ESPERA. Be sure to ask the driver where you should wait for returning buses, how frequently buses run, and especially the time of the last bus back.

A small trolley-train that takes visitors from the entry booths to various stops within the site, including the Teotihuacán museum and cultural center, runs only on weekends and costs 60¢ per person.

Archaeologists have discovered a 1,800 year old tunnel that leads to a system of galleries 12 meters below Teotihuacan’s Temple of Quetzalcoatl, the Feathered Serpent, in Mexico.

Spanning an area of more than 83 square kilometres , Teotihuacan is one of the largest archaeological sites in Mexico and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site . The city had nearly 250,000 inhabitants when it was at its height in the early 1st millennium AD. It also contains some of the largest pre-Columbian pyramids in the New World.

Spanning an area of more than 83 square kilometres , Teotihuacan is one of the largest archaeological sites in Mexico and is a UNESCO World Heritage Site . The city had nearly 250,000 inhabitants when it was at its height in the early 1st millennium AD. It also contains some of the largest pre-Columbian pyramids in the New World.